Wade Guyton

What we’re used to call his paintings are in fact large printed canvases, and it’s been so for more than twenty years now. Wade Guyton has long been considered an abstract painter, which he never claimed to be and even tried to avoid, using more and more imaged patterns (letters, fire, iconic furniture…). It is also relatively common to oppose, while thinking of his work but also in general, the physical to the digital, the printed to the file. But now that we all know that the digital is definitely not the immaterial realm we’ve been told it was in the beginning, but a host of hard drives, wires, servers and data centers, considering Guyton’s printer paintings as a way to resolve this dichotomy seems to lead to a dead end.

Pursuing the historical quest of producing a painterly trace without the hint of a gesture, in line as much with Martin Barré than with Andy Warhol, the American artist works with the digital materiality and seeks a manifestation of it that could be physically satisfying. And maybe that’s all we’ll grasp in the end, printed pixels and unprinted canvas.

We discuss that with him alongside many other things, such as the way we look at art, the way we read the news, and how important it can be to walk while looking at paintings…

Let’s start with the basics and talk about the pixels. They appear as a component not only technical but also notional in your printed works…

My paintings are made from digital files: in some cases, the file is overtly photographic, and in other cases, it’s a rectangle that I’ve filled with color, 100% black or less to create grey…

It’s more about the translation of that digital materiality into some other material form.

Zooming in on these paintings, it doesn’t tell you about the digital material, just its manifestation… It becomes a different kind of object that your body relates to.

It’s not like the language that tells us how to understand what an object is…

It would be more like a grammar for you, then…

So the rectangles, the black or grey ones, aren’t found images…

No, they’re just drawn in Photoshop and then filled. And in the paintings showing enlarged areas of the bitmaps, what we really look at is the unprinted areas. Most of these paintings are really just empty space. It’s really just exposing the blank canvas.

Wade Guyton, Untitled, 2016, Epson UltraChrome K3 ink on linen, 275×900 cm. Courtesy: the artist, New York, MAMCO, 2016. Photo: Annik Wetter — MAMCO, Geneva.

View of Wade Guyton’s exhibition, courtesy: the artist, New York, MAMCO, 2016. Photo: Annik Wetter — MAMCO, Geneva.

And what do you think of the pictures of these pictures, if I can say so? You’ve never thought of a digital show for example?

I make books all the time so I think of the reproduction of the paintings and of the difference between the experience of an object in real life and the representation of it in a book. And I design books knowing it’s a very specific experience. So far I haven’t made any digital books or exhibitions, but…

It’s interesting to me as I really see your work as a digital work, as something mostly related to the digital realm…

Maybe it’s an origin, but I’m not sure. I still deal with the physical world so much that, to me, a picture on Instagram doesn’t do the same thing as experiencing a ten meters long painting…

So the scale is for that purpose also? The experience…

Yes, I think so.

But for yours or?

Maybe me. Probably for other people too, but I’m the primary audience for my work, I guess.

Fifteen years ago, it was truly subversive to just print paintings…

I didn’t think of it that way, I was just trying to come up with a solution in my studio, to figure out how to make something. It’s hard to assess the radicality of something as you’re doing it.

Sure, and it’s not your job.

For me, it’s just the convergence of a very rudimentary digital experience and a real stubborn material experience. And maybe also because I’m from a generation that can clearly remember when there was no digital life.

And so am I. I’m right on the edge, people slightly younger than me don’t have this memory.

I don’t think I have anything intelligent to say about the digital. My understanding is always filtered through old fashioned material experience. Younger people probably have more to say about it.

And making so many books today, is this a kind of resistance?

Maybe. It does seem old fashioned. I like books.

But you’re not opposing books to digital media?

I don’t think so.

I read books online. I’m not opposed to figuring out a digital solution for a representation of the work, but I haven’t come across one that satisfies me yet.

Is this also a way to keep more control on the pictures of your work?

Museum Brandhorst, lower floor with works by Wade Guyton. Photo: Johannes Haslinger © Museum Brandhorst, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, München

I think very carefully about the physical experience of walking through an exhibition and so, for other people to understand that, photography is necessary. Thus I take photography very seriously to shape the encounter with the work. For me a book is a sequence of these particular views.

Actually, I came to these questions when I started to teach in an art school and was confronted to students who mostly “saw” shows on Contemporary Art Daily.

I also had this kind of experience once when I was doing studio visits with students and realized that they weren’t showing me any works that were in the room, but only pictures on their iPads. The works were actually in the room but they wanted to look at them on a screen.

And you don’t.

No. Not usually.

How do you feel when you see pictures of your work spreading out on the Internet?

Well, it depends on other people’s talent. But the Instagram or the Google Image experience is madness to me. It’s a bit frustrating because I see the work in a particular way.

But whatever, this is the world, it’s a very different experience than the one I would’ve shaped. You can’t control everything anyway.

So you always decide on the hangings?

I definitely decide on the hangings, yes. I’m involved in all aspects of my shows.

So how did you work with Nicolas Trembley? [the curator of the Mamco and of Le Consortium shows]

We had discussions in the studio, and chose things together.

View of Wade Guyton’s exhibition, courtesy: the artist, New York, MAMCO, 2016. Photo: Annik Wetter — MAMCO, Geneva.

But was it your idea to eliminate all the walls of the story in Geneva ?

I asked to take the walls down, yes, it came from me. Sometimes you can’t work with the preexisting architecture. For me, in this case, it was too claustrophobic. I needed some light, some air. And I wanted to see the structure of the building more clearly. And their windows, they’re amazing!

But the paintings were not made for this specific space, right?

The works were made before, in New York, but knowing the Dijon show was going to happen. Mamco was decided on later on after all the works were chosen for Dijon.

I think this iteration of the show is far more concentrated. The Consortium show was a physical experience of walking, walking, downstairs, upstairs… The way you walk through this space is almost compulsive, circular and the way you read the works thus is different.

And what about the Académie Conti pictures…

It was a totally different show, an independent idea. There was no connection between the Consortium one and Romanée Conti. The paintings were made specifically for this building that housed the wine storage for the vineyard. The house and garden have a very mysterious aura. And I knew not many people would see this show and if they did, they would have had to make a special trip.

But you showed your first “self-portrait” there… And now, at the Museum Brandhorst you’re hanging more explicit views of your studio than the ones that were made for the Dijon show and that we still can see at the Mamco, that is to say you’re showing the studio more like a place for activity than for display. Is there a specific reason for this apparition of humans in your images?

Nicolas Trembley took a photograph of me visiting the Académie Conti in the winter and, while I was thinking about the show, I went back to this photograph to recall the garden. And, in this moment, it made some kind of sense to let this image of the artist infiltrate the group of atmospheric grey bitmap paintings. It was a perverse decision I admit. At Brandhorst there are different studio views and some include people who work at the studio with me. The studio is an old cliché subject of painting, but it is also a blunt reality for me. And for this show I decided to show many diverse works that involved images of the studio, the assistants…

Wade Guyton Untitled, 2016. Epson UltraChrome HDR inkjet on linen, 213,4 x 175,3 cm. Photo: Ron Amstutz © Wade Guyton

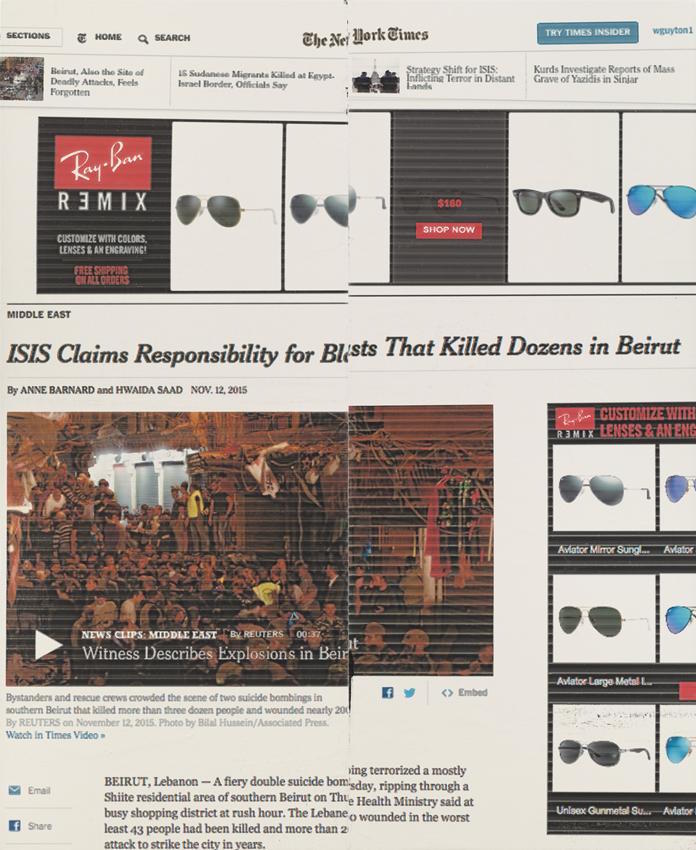

The issue of mundane images becoming paintings, from photographs for example, and then from paintings turning back to photographs, i.e. in a kind of circle from pixel to pixel, can at the same time be interpreted as extremely self-referentiated but also as a very general reflexion on the nature of image today, to put it in the manner of a cliché. Very recently, you started a new series of prints from The New York Times website (first shown at Petzel Gallery, New York, Nov.10 2016-Jan.14 2017). We’re more here in readymade images than you’ve ever been before, if I don’t get wrong. Is this a way to reverse the idea of still life in painting and to reduce this “space between what’s printed and what’s not printed” that you were mentioning earlier, though in a totally different meaning?

Wade Guyton, Untitled, 2015. Epson UltraChrome HDR on linen 84 x 69 inches. Courtesy Petzel Gallery, New York.

I started those paintings two years ago. They came about in between making more “serious” works. I regularly read the news throughout the day. And when reading it online, the webpage, the headlines, the ads, the comments all refresh and change. There are news alerts that punctuate the day. Often, this New York Times window would be open on the same laptop I am using to print the paintings, and one day I decided to print the news in that moment, probably for lack of another idea and also just to be “working”. They troubled me and over time I made more. The news of previous months would be constantly present in the studio. And, as objects, they antagonized the other works. This energy between a news painting and say, a monochrome, also antagonized me. I liked this. After a couple years of making them, I was convinced to do a small show of them at Petzel. I chose a group of them made from November and December of the previous year. What is compelling to me is how, as a viewer of them, myself, I am always having to resituate myself to “read” them—as text, as a painting, a photogram, as a briefly frozen image of material and information in flux, not even an object that is physically graspable.

And, on a completely different topic, I’d like to come back to your collaboration with Stephen Prina, is this still going on?

I think we have something like three more years! We just did the seventh one. Yes, it started seven years ago. I was a fan of his work and I wanted a work of his with spray paint, so I tried to buy one from the gallery but they wouldn’t sell it to me, so I just asked him: “if I make a painting, would you spray paint on it? I could make two paintings, you could spray on both, and then we could trade.”

He liked the idea.

Then Friedrich Petzel heard about it, and said we should do it in the gallery. So we did it once.

Then someone was interested in buying one of the paintings, but the show was over and he asked if we could make another one. But we thought: “we can’t just make one, we have to redo the exhibition.”

And I guess at some point we said that ten was a good round number. So every year it happens in the gallery and everything is installed exactly the same way. The first instance, the gallery was on the 22th street but, a few years later, it moved to the 18th street. The configuration stayed the same, but it doesn’t quite fit in the new gallery the same way. The new gallery put pressure on the installation and one painting has to sit on the floor.

Apart from this specific link you maintain with Prina, do you feel part of a scene in New York? I mean, are there artists, painters, with whom you could regularly meet and discuss painting for instance?

I don’t really talk about painting so much…

This conversation happened on the occasion of the following European shows of Wade Guyton:

Le Consortium, Dijon, June 25 to September 25, 2016.

Mamco, Geneva, October 12, 2016 to January 29, 2017.

Museum Brandhorst, Munich, January 28 to April 30, 2017.

Forthcoming: Writings on Wade Guyton, published by JRP|Ringier, edited by Tim Griffin.

Texts by Daniel Baumann, Johanna Burton, Bettina Funcke, John Kelsey, Vincent Pécoil, Scott Rothkopf, et al.

(Image on top: Wade Guyton, Untitled, 2016, Epson UltraChrome K3 ink on linen, 325,10 x 274,30 cm. Courtesy: the artist, New York. Photo: Annik Wetter — MAMCO, Geneva)

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Paolo Cirio, Sylvain Darrifourcq, Computer Grrrls, Franz Wanner, Jonas Lund,

Related articles

Céline Poulin

by Andréanne Béguin

Émilie Brout & Maxime Marion

by Ingrid Luquet-Gad

Interview with Warren Neidich

by Yves Citton