Céleste Richard Zimmermann

From the studio.

A visit to the studio of the young artist Céleste Richard-Zimmermann, located in a former garage in the Dalby district of Nantes, is an instructive way of appreciating her commitment. Everything here is teeming. On two walls of the studio: polystyrene bas-reliefs representing hybrid characters, axonometric drawings, sketches, a template for creating the decorative motif of a column, notes of intent. On his makeshift desk, a computer surrounded by boxes, books and various brochures. Three bronze-coloured plaster dogs on a tray are being repaired. Finally, on the shelves, paint pots and flammable and toxic chemical cans are piled up in no particular order. The artist’s energy, reminiscent of Niki de Saint Phalle, is evident here, as is her desire to evoke her recent residencies abroad at Budapest Galéria (1) and in Recife, Brazil (2), which have opened up new creative horizons for her.

Addressing Céleste Richard-Zimmermann’s preoccupations plunges us into a millefeuille whose semantic thickness expands as we question her works. The collective memory, the social, the political – in a symbolism that permeates both iconography and visual art, drawing on the sources of heterogeneous cultures and eras – are summoned up in no particular order. Like other artists of her generation, she likes to use narrative, fiction, anecdote and news items to create works imbued with the chaos of our time.

Crédit : Grégory Valton

Deviant cynophilia.

Born in Mulhouse in 1993, Céleste Richard-Zimmermann entered the Fine Arts School of Nantes in 2012 and obtained her DNSEP in 2017. While working in the theatre as a set designer, her exhibitions have followed in rapid succession: “Polder II” at Glassbox in Paris, the Biennale de la jeune création in Mulhouse and “Le cœur des collectionneurs ne cesse jamais de battre” at L’Atelier in Nantes (2018). His work quickly attracted attention, as in the exhibition “conte the-ogre.net” at the Suzanne Tarasieve gallery in Paris (2021), where the artist presented “Le Temps des cerises”, a three-metre-high column sculpted in polystyrene which, in an upward movement of struggles between CRS and biting dogs, ends with the engraved inscription “NI DIEU NI MAÎTRE”. Then, for his second solo show at the RDV gallery in Nantes, entitled “CAVE CANEM” – the title of which is taken from the eponymous inscription on the mosaic on the threshold of the house of the “Tragic Poet” in Pompei – the artist presented a monumental fresco in polystyrene, The bas-relief again depicts battles that evoke the frieze on the Treasure of the Cnidians in Delphi and the Art Deco colonial frescoes by sculptor Alfred Janniot on the façade of the Porte-Dorée palace in Paris. Clearly, the artist is trying to plunge us into a world of social chaos in which underprivileged people depicted as dogs confront helmeted policemen equipped with asexual armour taken from the Staircase of the Giants in the Doge’s Palace in Venice. The metaphorical use of animals, reminiscent of the fables of Aesop and La Fontaine, is full of ambiguity. Not only is the material far from eco-responsible, but the moralising virtue is absent to give free rein to a polysemous and disruptive interpretation. Isn’t the dog, symbol of loyalty and therefore kindness, also the fearsome guardian of private property? Is the riot not the result of a pack governed by a Pavlovian reaction?

Other polystyrene columns, presented at the exhibition of the winners of the City of Nantes prize (3), such as Ronces – whose shaft is decorated with the geometric motif of a wire fence and topped by a capital echoing the motif of concertina barbed wire, reputed to be impassable – enrich this collection of architectural fragments. The artist slips in a number of references: pictorial – such as the dog defecating on a pedestal, a familiar motif in eighteenth-century Dutch painting – or cultural – such as the pliers reminiscent of one of the tools used by Arma Christi or anti-capitalist activists.

With Verbunkos dog, presented in Budapest, the artist is developing a ceramic sculpture whose legal source refers to a 2011 law aimed at registering dogs in Hungarian municipalities in order to tax dog owners other than those of Hungarian origin. This anthropomorphic work takes on a political connotation that illustrates the grotesque consequences of the surreal ideology of “national preference”.

Céleste Richard Zimmermann’s obsession with dogs does not stop with these sculptural representations, as if no single technique could satisfy his quest to unveil this motif. This was the case in 2017, when, during a road trip in the United States, she developed the R.A.T.S project, which led to the creation of a video, From Dogs to Gods (4), accompanied by five ceramic dog heads documenting the practice of a New York rat-hunting club with dogs. The monstrosity and cruelty revealed in this way strike at our certainties, which generally assign hunting to rurality. Ambiguity is also present in this photographic mise-en-scène in which a dog, referring to the Negro Matapacos (5), leaps up to seize a polystyrene truncheon as his bone to gnaw. Similarly, Céleste Richard-Zimmerman uses painting as a way of breathing to accompany her sculptural practice. Here again, as in the painting Le Massacre des Innocents (2017), painted on wood in grisaille and influenced by the work of Pieter Brueghel, a menagerie grappling with a human crowd armed with sulphate guns is active in exterminating skits. In other paintings on acid-etched metal, the artist amuses himself by depicting a world of hybrid porcine figures playing perverse games, or, more recently, an Anthropocene herbarium composed of particularly flammable flowers that evoke the ‘burning bush’ where incendiary ghostly sowers intertwine.

8 céramiques emaillées et 5 plaques de granit sérigraphiées

Crédit : Vinas Vincent

collection privée, collection artdelivery et collection de l’artiste

Shared alcoholism and opera buffa.

In 2023, having just returned from her residency in Recife, Céleste Richard-Zimmermann is already in the process of completing a piece whose status is closer to design. This piece, commissioned by the brand new Scroll art gallery in Nantes, is intended to occupy the reception area and serve as a desk. Appearing to emerge from the wall and floor, this pearly grey resin sculpture resembles a giant mushroom from a children’s story. Through a phenomenon of pareidolia, it metamorphoses into a language, a place of taste and language, but also a sign of defiance, contempt or mockery.

But let’s return to his residency in Brazil. The starting point for his research, which was quite ordinary, was his ‘encounter’ with cachaça, the Brazilian alcohol obtained by distilling vesou, a sugarcane extract. The result was the creation of a potlatch, one of the artist’s works about sharing. However, while it evokes drunkenness, it appears anthropomorphic, like Rebecca Horn’s painting machines, where the alcohol circulates – like blood – through pipes connected to bas-reliefs representing pioneer plants (6) made from rapadura, unrefined brown sugar that slowly dissolves – like the ritual of absinthe drinking in Cubist Paris – and ends up in cups that patient spectators are invited to drink. This passage from the work to the viewer’s body has something religious about it, reminiscent of the experience Yves Klein had his public undergo when they were invited to drink a blue cocktail, a beverage composed of gin, Cointreau and above all methylene blue, during his exhibition “La Spécialisation de la sensibilité à l’état matière première en sensibilité picturale stabilisée” (“The specialisation of sensitivity in its raw material state into stabilised pictorial sensitivity”). See and then drink, to move into a modified state of consciousness. The work also resonates with the efforts of researchers and spiritual leaders in indigenous communities to solve the problems of alcoholism present in Mbyá-Guarani communities. It is clear, according to the artist, that this intense experience will enable her to envisage more ambitious projects in the months to come.

This interest in sharing, inherent in relational aesthetics, was already present in 2017 when she produced a performance for her diploma at the Fine Arts School in Nantes, in which chocolate mouldings – an addictive substance like alcohol – representing Molotov cocktails and pebbles were broken in a vice and then eaten at the risk of a liver attack. These objects of revolt or revolution, sweetened by candy and finally destroyed, symbolise the destiny of commodity fetishism, but also of the work of art. Similarly, in 2019, during the one-day solo show “MAKE CORN BLUE AGAIN (7)”, the guests metamorphose into chickens, into frenzied consumer fowl, who pounce on the popcorn laid out in troughs bathed in UVA rays reminiscent of tanning booths. Reinforced by the sound of the popcorn popping, the exhibition space is transformed into a cinematic setting for a new fiction. We understand that for Céleste Richard-Zimmermann, art must maliciously transform spectators, inviting them to choose between reification and emancipation.

Mousse polyur.thane, cendre de v.g.taux / polyurethane foam, plant ash, 10 m2 env. / approx. OEuvre produite par / produced by Le Carré, Scène nationale – Centre d’art contemporain d’intérêt national. Photo : Marc Domage.

Chthonic gardening.

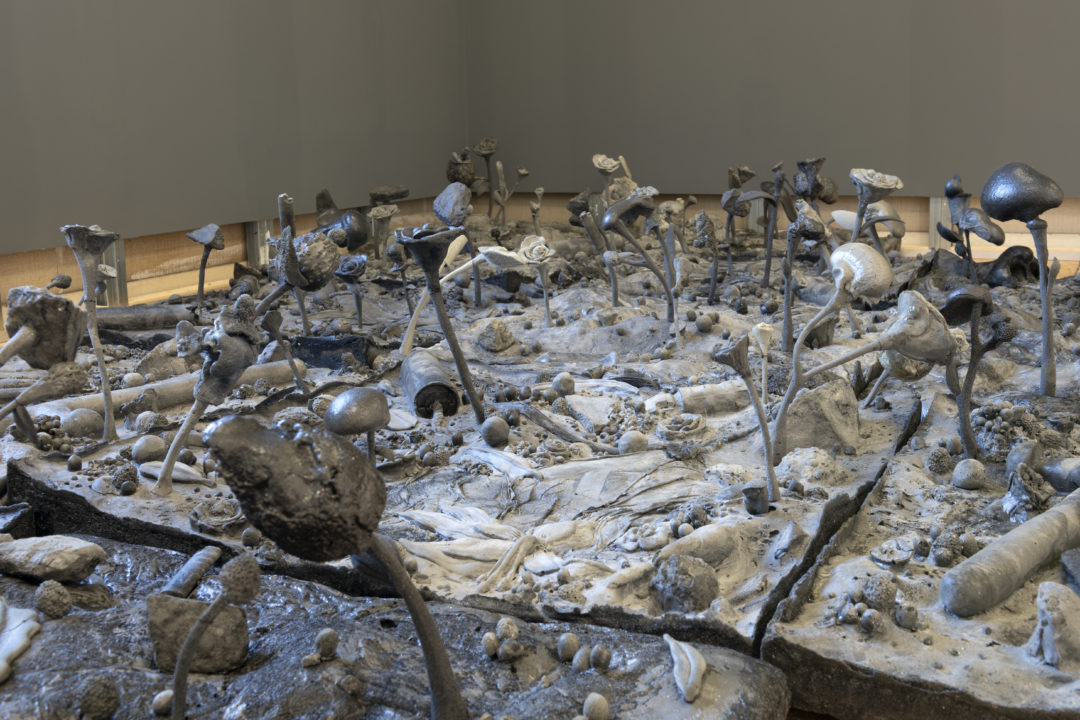

At her latest exhibition, “Tout brûler, tout semer”, at 4bis, Château-Gontier (8), high-relief slabs colonise the floor. Moulded in tinted polyurethane foam, they form a post-apocalyptic garden reminiscent of Grafted Garden (Pollution-cultivation-new ecology) by Japanese artist Tetsumi Kudo. The artist conjures up an archaeological perspective that reveals footprints, handprints, nose and eye models, charred real or artificial flowers and foliage, casts of truncheons and Molotov cocktails, and rocket-propelled grenades. It’s at this point that confusion sets in. A battlefield, this pessimistic pavement could rise from its ashes and become a Chthonic garden (9). The road to hell is paved with good intentions!

Erecting monuments.

Céleste Richard-Zimmermann’s work is a monumental memorial, full of fabulation, filled with eclectic literary, cultural and artistic references ranging from Ancient Greece to the Middle Ages, via Dutch art, Art Deco and contemporary art. Not without a sense of humour, she invites us to question our inner convictions, like the ancient cynics. Her imposing works, in mediums mostly derived from the petrochemical industry that many ecofeminist artists would refuse to use, nevertheless emanate a disturbing Zeitgeist.

Bas-relief sur polystyrène oeuvre soutenue par les Factotum

Crédit : Philipe Piron

1« Lost Dog United », Budapest Galéria, 2023.

2crossed residency with Paradise (https://www.galerie-paradise.fr) and exhibition « Loi 2011 Exonération d’impôts sur les chiens » ???, Recife, 2023.

3 Philippe Szechter, “L’Entre-zone, L’Atelier, Nantes”, Revue 02, 101, 2022.

4 R.A.T.S refers to the members of the Ryders Alley Trencher-fed Society. See also From Dogs to Gods on Vimeo.

5 Negro Matapacos (Black Cop Killer) famous black stray dog with a red scarf, companion of the student protests in Santiago, Chile in the 2010s.

6 The first organisms to colonise an environment after a natural disaster.

7 Yves Klein, “La Spécialisation de la sensibilité à l’état matière première en sensibilité picturale stabilisée”, known as the “Exposition du vide”, Galerie Iris Clert, Paris, 1958.

8 Rémi Baert, Manger les grillots avec le tac-tac, 2019, online at lacritique.org.

9 Temporary exhibition space at Le Carré, scène nationale – centre d’art contemporain, Château-Gontier.

10 Chthulucene is defined by Donna Haraway as a world of compost, “a thick time for chthonians”.

______________________________________________________________________________

Head image : « Martyre décorum » – 2020 – bas relief – polystyrène – 6mx3m30x15cm

Oeuvre soutenue par la Région des Pays de la loire

Credit : Gregory Valton

- From the issue: 108

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Fabrice Hyber,

Related articles

Iván Argote

by Patrice Joly

Laurent Proux

by Guillaume Lasserre

Diego Bianchi

by Vanessa Morisset