The techno-vernacular movement (pt.1)

Shedding new light on the insights of vernacular practices in the era of new digital technologies.

“I turn on my made-in-China LED therapy mask and set it to a green light frequency. I was told that I should irradiate myself in green if I want to see what a plant sees.”

In our hyperconnected, techno-driven world with its push to ‘go paperless’, there is a renewed interest in handmade or locally-sourced goods, ‘digital detoxing’, alternative medicine and new-age practices. Like Chilean artist, activist and educator Patricia Domínguez, more and more people are seeking out ways to live a hybrid lifestyle where Made in China meets artisanal techniques and ancestral teachings begin to appear on our smartphone screens. What we will refer to here as techno-vernacular transcends the polarity of a future-oriented, technology driven world with its homogenising effects on culture and one which is marginalised, focused on the past and its vernacular practices and traditions.

To begin with, technology is a set of tools, insights and practices founded on scientific principles. Assumed to belong exclusively to the domain of humans, technology is used for the optimisation of the extraction of resources, for production purposes, for knowledge and informational transfers. Subject to a principal of use and obsolescence, of introduction and decline, new technologies are a reflection of modernity and its exponential scientific innovations. Those who use them are seen as being progressively on the cutting edge of technology, then up-to-the-minute, then behind the times, as seen from a temporal, linear, Westernised perspective.

By contrast, vernacular refers to that which pertains to a particular community. It designates that which belongs to a specific location, to the local population; what is native or indigenous. The vernacular is closely related to folklore, which is the ensemble of collective practices emanating from a community and which is transmitted from one generation to the next through oral transmission or imitation: folk tales, music, beliefs, rites, costumes, dances, techniques, etc. The vernacular denomination for a given plant or animal opposes the given scientific denomination because it is a local denomination given in the native language. Seen through the lens of western scientism, vernacular techniques are often judged as primitive, originating from a world whose bygone era is economically non-viable. To associate oneself with this would be the equivalent of a rejection of modernity and globalisation.

As claimed by artist, farmer, doula, kundalini and kemetic yoga instructorTabita Rezaire, “[…] the tension lies within ‘scientific knowledge’, as the hierarchy between systems of knowledge imposed by coloniality only considers Western rationalist / logic / ‘proven’ knowledge as scientific. When you detached from these racist biases and allow other cultures of science to exist, then the meaning and scope of what technology can be expands radically.” A new generation of artists is showing the potential fecundity of the porosity between the technological and the vernacular. Through the works of some techno-vernacular artists, we may see how their creators are shedding new light on heretofore marginalised ancestral insights by fusing them with the references of younger generations on TikTok.

The Awakening of the Neo-Indigenous

The silencing of the vernacular of native insights took root the colonial era and persists today via a colonialism which makes up our economic and political systems. Modern western constructs have since been considered living examples—of entertainment, of consumption—and promote an ontological approach to the world. These forms of domination impose themselves, whether brutally or insidiously, as replacements for ancestral practices.

One telling situation is that of the Canadian First Nations who fell victim to European conquest of their territories near the end of the 16th century. These populations have become, despite the creation of reservations and the restitution of certain territories, strangers in their own degraded ancestral lands. Faced with this exclusion, the native Canadian artist collective New Red Order (NRO), whose core contributors include Adam Khalil (Ojibway), Zack Khalil (Ojibway) and Jackson Polys (Tlingit), rehabilitate these communities and lead the initiative for an indigenous future. “This frustration we have felt when faced with Native-related politics in North America, or even worldwide, comes from our preoccupations being constantly interpreted as a kind of return to something which can no longer exist. But even though not everyone may want to go live in a wigwam, we would nonetheless like to feel at home here. Return our land to us.”

In order to recrute allies and to form a new, more hospitable environment for contemporary indigenousness, instead of for an imaginary entity from a savage past, NRO has assimilated methods and techniques from the marketing milieu. For their multifaceted project, “Never Settle” (2018-), participative installations and recruitment campaigns invite the visitor, as potential recruits, to submit to an initiation. One of the resulting videos, Never Settle: Calling In (2020), enlists the non-indigenous, in the style of a political campaign spot, to participate in a public secret society for a real postcoloniality. Behind its music and generic advertising images, Never Settle: Calling In attempts to identify an inappropriate vision of indigeneity: one based on commodification and exoticisation and decontextualised appropriation, in order to make inroads for the expansion of indigenous action. The guilt of occupying colonials is beside the point faced with the future of their communities, the one they will build with the means and strategies currently at their disposal.

This political project allows for an indigeneity which is adapted to urban, globalised realities to exist. It uplifts the Neo-Indigeous: silenced communities which are capable of reclaiming control of their cultural ancestral capital in the face of colonialism.

On the other side of the world, this narrative of western oppression is equally challenged by the Slavs and Tatars collective (founded in 2006, in Eurasia). The collective celebrates cultural syncretism on the Eurasian continent—from the Berlin wall to the Great Wall of China—while attacking Western desire for the absolutisation of a common temporality. Like NRO, the multi-sensorial Dillio Plaza (2019) resulted from a research project centred around fermentation, “Pickle Politics” (2016-), taking on the form of a promotional space for the fermented juices of pickles and cabbage, while also doubling as a space for relaxation. Posters, automatic juice distributors, vertical blinds, fountains and green plastic lawn chairs: in this promotional space, the fermented juices are marketed as luxurious wellness products. There are echoes with the recent assimilation of fermented products into major supermarket chains such as with luxury perfumes and electrolyte drinks. Paradoxically, fermentation is a vernacular ancestral practice, common in particular to Turkish nomadic tribes (7200 B.C.). As Slavs and Tatars have stated: if pickle juice has been sold in the United States as a sports drink since the 2000s, in Eastern Europe it has long been considered a traditional cure for hangovers. In opposition to a linear, monolithic cultural history imposed by capitalism it celebrates cultural heterogeneity. The Pickle Bar is one manifestation of this approach—a space for reflection and interaction where Slavic fermented delicacies are served alongside vodka.

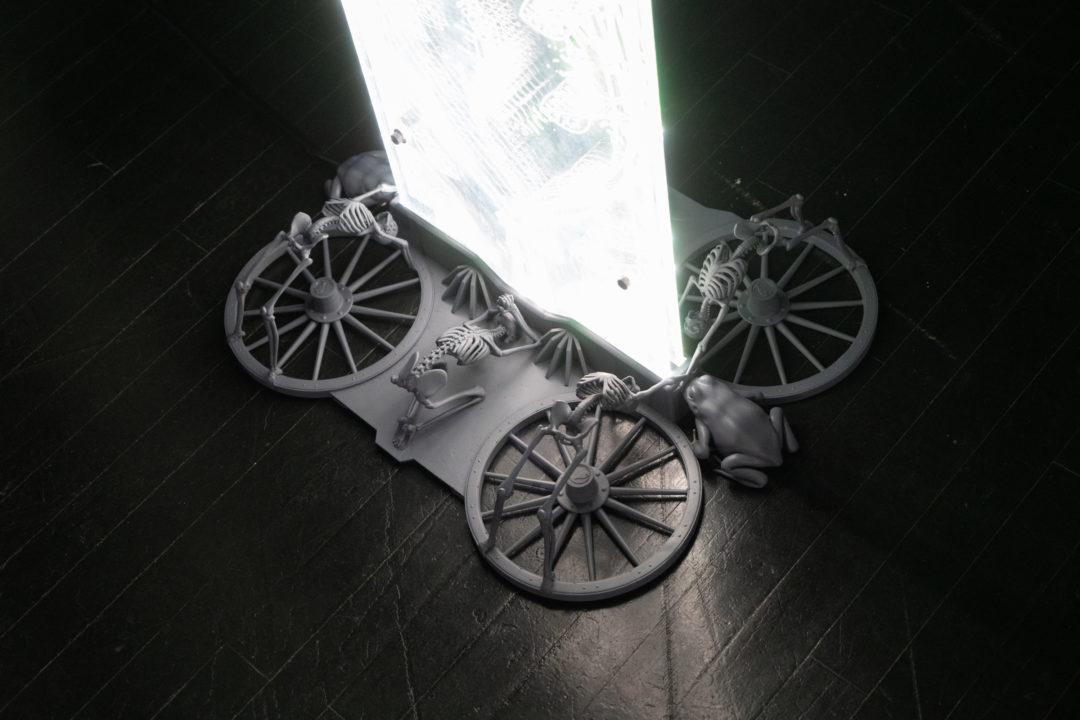

The struggles against homogenisation and for the conservation of traditions have been highlighted by many techno-vernacular artists. The Kuwaiti artist Monira Al Qadiri (1983, Dakar) studied in Japan and is now based in Berlin. The artist produces iridescent works which fuse petroleum with pearl, questioning the meteoric emergence of petroleum economies in the Persian Gulf and the decline of tradition in the region. In the video Diver (2018), the movements of synchronised swimmers in black waters are paired with the voices of pearl fishers singing Kuwaiti songs, some of which date back to nearly 800 years ago and have slowly been forgotten with the waning of the trade, save for when they are revived for tourists. The artist’s grandfather was himself a singer on pearl fishing boats. The performers swim and twirl around to the point of exhaustion, like the circular movement of oil drills opening up new petroleum wells to the point of the exhaustion of resources. Like Al Qadiri, other techno-vernacular artists put their fingers on the pulse of concomitant phenomena of environmental degradation and the disappearance of certain human knowledge bases.

From Indigenous Immanence Toward Spirituality as Technology

Western societies, whether agrarian or sedentary, encourage an anthropocentric vision of the world, placing human beings at the centre of the organisation of living things. The appearance of monotheism (circa 1500 B.C. – 600 A.D.) introduced the concept of a transcendent god, reinforcing this vision and tended to dispossess nature of its spiritual agency, as it had once been seen by animistic populations of hunter-gatherers or foragers etc. The vernacular practices of these populations are considered non productive and incompatible with the establishment of an all-powerful human race. Nonetheless, ritual and spiritual practices which are oriented toward nature were essential in the development of an ecological consciousness on a local and community level, even before the appearance of the word ecology. In many of these societies, humans are seen as being on the same level as other living beings. The destruction of one part leads to the loss of the whole: the world is made up of predecessors, as opposed to resources. Animism and non-dualistic spiritual beliefs like Buddhism, Hinduism and Taoism reject strict oppositions between nature and culture, human and non-human, spirit and matter, body and soul. They emphasise their interdependence, their immanence. Could works by techno-vernacular artists plant the seeds for ancestral and hybrid forms of indigenous immanence?

Timur Si-Qin (1984, Berlin), whose practice envisions a space for environmental concerns within spirituality, refers to the secular care given by indigenous societies in order to maintain a healthy equilibrium and prevent further destruction of the environment: “Westerners have awoken to their own moderate scale of environmentalism only in the last few decades, and this trend must accelerate in order for us to have any hope of facing the challenges of climate change and biodiversity collapse. Although Indigenous Peoples make up only 5% of the global population, they manage more than one quarter of all land on the planet while protecting about 80% of global biodiversity.”

Timur Si-Qin, who is based in New York and is of German and Mongolian-Chinese descent, grew up in Berlin, in Pekin and in an Apache community in the Southwestern United States. The artist became known as part of the post-Internet movement in the early 2010s. In 2016, he created New Peace, a long-running work which takes the form of a new protocol, and is both a “branded ecosystem” and a form of spirituality which is symbiotic with nature. In his installations which are made of organic structures and his virtual reality (VR) environments and offshoot products, he uses computer-generated images and marketing techniques. These cognitive materials build an empathic bridge between us and that which is non-human in order to reconnect us with our environment. New Peace fills the western world’s growing spiritual void. Two points of departure inform Si-Qin’s practice. First off, spiritual traditions and religions are a many-thousands-of-years-old form of technology which provide communities with protocols to adapt their behaviour to their local environment. Secondly, art is a form of secular religion connecting individuals with one another, uplifting diversity, while eliciting collective emotions. The artist uses his website, publications and online conferences to spread the values of this new spirituality inspired by animistic societies, Taoism and rooted in urgency—particularly with regard to the environment—of the present-day.

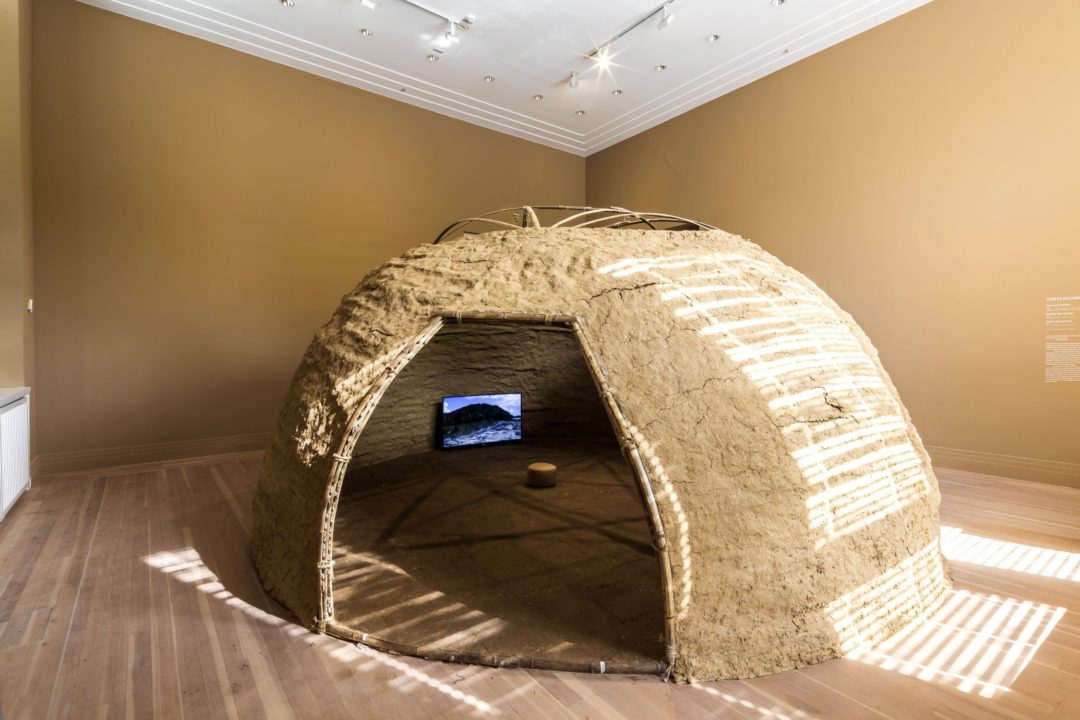

Tabita Rezaire (1989, Paris) writes in Conscience u.terre.ine, “By engaging with African and indigenous ancestral technologies of information and communication, we dare to reconcile the worlds of organic matter, energy and electronics to nurture a mystico-techno-consciousness. So we sing to decolonize and heal our technologies.” In 2020, Rezaire opened Amakaba, a centre dedicated to Earthly, corporeal and sky wisdom in the Amazonian forest of the Guianas. Art, science and spirituality meld in projects which integrate agroecology with cocoa production, as well as solstice and equinox rituals which nourish the connection between earth and sky. Plant, moon and feminine cycles alike are lauded, with the objective of collective healing and the transmission of ancestral wisdom. Women’s cycles—from menstruation to maternity, as well as the womb as the original technology are all honoured. Amakaba has cultivated a network of doulas in Guyana which is attuned to ancestral teachings which recognise childbirth as a rite of passage which has been present for millennia. For Farmer’s Wisdom (2022), an installation which resulted from research conducted at Amakaba, a gigantic hive-hut made of straw-clay houses four videos. Guyanese farmers discuss their relationship with the land, through the cultivation of cocoa, medicinal plants, beekeeping and traditional native method of abattis. (Translator’s note: The word abattis can be loosely translated as ‘field’ however in the South Guyanese region the term references a larger practice of slash-and-burn agriculture. Reference: https://www.parc-amazonien-guyane.fr/fr/des-connaissances/une-terre-en-mutation/les-systemes-agraires-du-sud/labattis-brulis-itinerant) They also discuss the larger implications of the upkeep of the land, such as the development of autonomous subsistence methods and provide recommendations and guidelines for future generations.

1 Patricia Domínguez, Technologies of enchantment. When a ceramic vase and a drone cry together, Gasworks, Royaume-Uni, 2019, p. 19.

2 A doula is someone who accompanies and gives support to pregnant people and their entourage during the prenatal and postnatal periods, alongside medical care, as well as during transitionary periods, such as during menopause or following the loss of a loved one.

3 Indian yoga with a spiritual dimension.

4 Yoga with a spiritual dimension originating in Egypt in the 1970s, inspired by ancient Egyptian philosophy and positions observed in the figures in hieroglyphics.

5 New Red Order (as told to Giampaolo Bianconi), « New Red Order on channeling complicity toward Indigenous futures », ARTFORUM, October 2020, https://www.artforum.com/interviews/new-red-order-on-channeling-complicity-toward-indigenous-futures-84189.

6 See: Stephen T. Garnett, Neil D. Burgess, Julie E. Fa, et al. « A spatial overview of the global importance of Indigenous lands for conservation. »,in Nature Sustainability, Vol I, juillet 2018, pp. 369-374.

7 Timur Si-Qin, Heaven is Sick (excerpt), 2020, p. 20.

8 “Decolonial healing: in defense of spiritual technologies”, in Conscience u.terre.ine, Les presses du réel et Espace multimédia Gantner, France, 2022, p. 155.

9 In situ artwork co-created with thirty students from the Natural Building Lab in Berlin at Gropius Bau for the workshop Beehive — Natural Building Lab (nbl.berlin).

10 Tabita Rezaire, « Singing Bee Garden » (2021), « Cacao d’Amazonie » (2021), « Jardin Bois de Rose » (2022), « Terre Rouge » (2022).

______________________________________________________________________________

Head image : Slavs & Tatars, Dillio Plaza, 2019.

Courtesy Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin. Photo : Luca Giardini

- From the issue: 104

- Share: ,

- By the same author: The techno-vernacular movement (part.2),

Related articles

Paris noir

by Salomé Schlappi

Some white on the map

by Guillaume Gesvret

Toucher l’insensé

by Juliette Belleret