Post Human

“Redefining life”, Post Human, twenty years later

As a research tool that is as necessary for curatorial studies as it is for art history, the principle whereby exhibitions can be reproduced recently focused on a certain number of canonical exhibitions, both in archival shows and in shows that are literally identical to the originals. There are also less known and less analyzed examples, which have nevertheless also marked their times and influenced minds. In this respect, we must make mention of “Post Human”, a series of exhibitions organized by Jeffrey Deitch in 1992,1 which took a close look at the way “figurative art”2 was reacting to biotechnological and computer advances, as well as changes in post-’68 human behavioural patterns, fundamentally challenging humanist principles. Without “reproductions” as such being strictly speaking involved, many recent shows3 raise similar questions and are part and parcel of the continuity of Deitch’s project, even though he is neither directly quoted or referred to. More than twenty years have passed since 1992, which might imply major changes and thus legitimize the renewal of a project that is, on the face it, socially, technologically and conceptually null and void. To consider “Post Human” as such would, however, be a mistake: the questions arising from its ideas are undeniably relevant to this day, as if, paradoxically, when technology and the human sciences have been evolving apace ever since, we were at the same point, ontologically speaking.

Installation view of “ProBio”, part of “Expo 1: New York” at MoMA PS1, 2013 (works by DIS and Alisa Baremboym). © MoMA PS1; photo: Matthew Septimus.

This series of questions tallied with a scrupulous analysis of the condition of western man in the early 1990s. Like many others, Deitch asserted that it was henceforth quite normal to oppose Nature in order to re-invent oneself, thanks, in particular, to plastic surgery (very much on the rise at that time) and to the incorporation of technological progress. Genetic reconstruction challenged the foundations of Darwin’s natural evolution, because human beings could choose how they wished to evolve. Deitch stressed the changes at work since the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, such as the end of Eurocentrism and patriarchy, the globalization under way, the shattering of gender categories, and the interchangeability of identity, all contributing to the radical alteration of the subject. The computer world and cyberspace brought in a new perception of space-time, giving rise to a new structure of thinking perceived as irrational. Lastly, he underscored the fact that human relations would in the future be greatly affected by technology, and would appear more virtual than real.

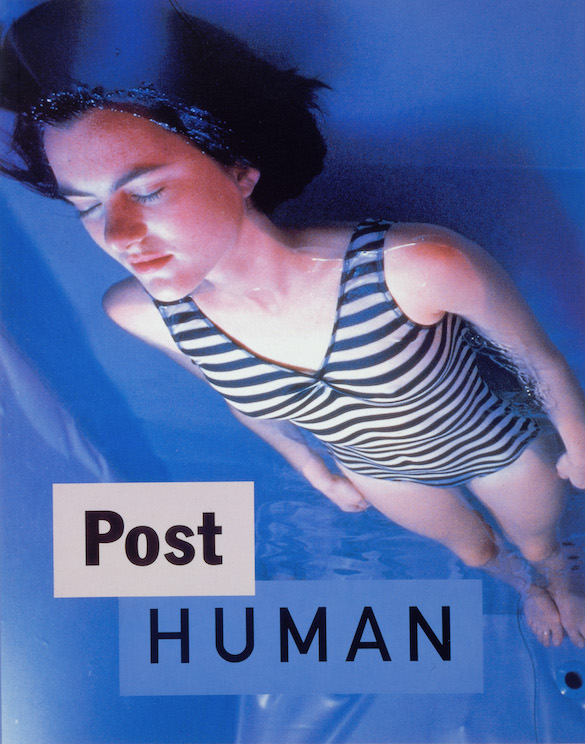

Post Human catalogue cover, designed by Dan Friedman, 1992, © DESTE Foundation.

These considerations were dependent on, among other things, the observations of Ihab Hassan, regarded as one of the earliest theoreticians to have used the term “post-humanism”: “We need first to understand that the human form […] may be changing radically, and thus must be re-visioned. We need to understand that five hundred years of humanism may be coming to an end, as humanism transforms itself into something that we must helplessly call posthumanism”.4 Hassan at that time noted that the obsolescence of the humanist subject (white, male, rational, anthropocentrist…) as well as the dissolution of the dichotomies peculiar to classical humanism such as subject-object, man-machine, science-culture… “Will artificial intelligences supersede the human brain […]? We do not know. But this we do know: artificial intelligences […] help to transform the image of man, the concept of the human”.5 J. Deitch’s project in fact introduced in-depth thinking about the consequences of these changes on the conception of the subject: what, in concrete terms, would the post-human look like, and in what social environment would it evolve? Deitch remained visibly neutral and offered no opinion, even though a slight apprehension can be detected in his argument, not to say an anxiety about possible aberrations to come: “There is a sense that we are advancing but not progressing, mired in a swirl of unexpected side effects that have undermined our belief in a rational order and moved us closer to embracing an irrational model of the world.” Within his uncertainties, “what we do know is that we will soon be forced by technological advances to develop a new morality.”6 This urgent need for a “new morality”, which would then act as a safeguard against possible threats, betrayed on the one hand the fear caused by speculations, across the board, about the future and integrity of the human species.

In reiterating the issues raised by “Post Human”, several recent exhibitions give off the same kind of anxiety about the future development of human beings. The Post Internet Survival Guide (2010) project—at once blog, travelling show and catalogue devoted to the flows of on-line images and information—was undoubtedly one of the first to appropriate these themes (the Internet was already the object of several observations in “Post Human”). The wording in the catalogue’s introduction, such as “The notion of a survival guide arises as an answer to a basic human need to cope with increasing complexity”—calling Deitch’s “new morality” to mind—and “This is the space where we ask ourselves what it means to be a human being today”,7 might easily paraphrase that of Post Human. Three years later, the artist Josh Kline came up with the exhibition “ProBio” (2013) at the MoMA PS1: visiting “the theme of dark optimism within the context of the human body and technology”, the works explored “the continuing radical impact that technology has upon the human body and the human condition”. What is involved here, once again, is a revision of Darwinism in the face of the progress of biotechnology, computer science, and a world in which “the distinctions between living organisms, information, objects, and products become irrevocably confused”.8 If dark optimism makes reference to a line of thinking consisting in determinedly confronting the harsh reality in which the world is currently embedded, in order to oppose it with an unfailing belief in humanity’s reactive potential, “ProBio” seemed more “dark” than optimistic. Partly or dimly lit, the show gave off a disturbing atmosphere in which the post-human seemed broached from the angle of a progressive annihilation of the human species. The human body was present in it, but represented as dismembered and exploded, thus becoming the guinea-pig for extremely sophisticated scientific experiments. DIS’ Emerging Artist (2013) presented women at the end of pregnancy, whose faces never appeared in the field of the image. They were thus reduced to the status of surrogate mothers of embryonic new artists, and to presence-less reproductive objects. Josh Kline, for his part, reintroduced the human head, but this time around without any body, and technologically modified, with the series Architect’s Head with Ergonomic Design (2012-13). Dina Chang’s Flesh Diamonds and Alisa Baremboym’s Porous Solutions (2013) gave the impression that bits of human flesh had mutated with unrecognizable objects during ethically uninhibited experiments, undertaken by laboratories that were more concerned with their commercial results than with the integrity of the human body. In Ian Cheng’s Abax Siluria (2013), all that remained were fragments of prosthetic machines bogged down in a tank of non-conductive mineral oil, thus letting them move about obtusely in this post-apocalyptic residue. Small hoover-like robots, cleaning the floors of the exhibition rooms, created a feeling of paranoia among visitors. Also produced by DIS, I Feel works (2013) ape the robot vacuum cleaners of certain large firms, meant to clean office areas, but which also collect employees’ DNA, so the employees thus become subjects for potential controls. This presentation illustrates Josh Kline’s latent pessimism with regard to post-humanity, which he admits by mainly associating it “with the relentless push to squeeze more productivity out of workers – turning people into reliable, always-on, office appliances.”9 The artificial turning-point of biology does not seem to bode well, either, according to “ProBio”. Georgia Sagri’s installation Williamsburg (2013) refers to the growing number of gardens appearing on the roofs of Brooklyn during the recent wave of ecological awareness. This garden nevertheless introduced a certain degree of doubt caused by yellow and dehydrated plants, reducing to nothing the hope of obtaining resources coming from a recently re-created nature.

Timur Si-Qin, Premier Machinic Funerary: Part I, 2014 (detail). Tension fabric display, plexiglass vitrine with LEDs, 3-D-printed bones, flowers, variable dimensions. Courtesy the artist and Société, Berlin. Installation view of the Taipei Biennal “The Great Acceleration”, 2014.

Stewart Uoo, Security Window Grill VII, 2014. Steel, enamel, rust, silicone, acrylic varnish, human hair, 46 × 91 × 38 cm. « Inhuman », Fridericianum, Kassel, 2015; © photo: Achim Hatzius.

In this way, the disarray ushered in by “Post Human” carries on and, despite a somewhat guaranteed textual entrance as far as humanity’s future is concerned,10 the exhibition “Inhuman”, on view this spring at the Fredericianum in Kassel, does not artistically manage to get beyond the collective angst created by the post-human. This project takes cognizance of the same technological and social mutations as those analyzed in “Post Human”, the ones which force us to “rethink the constructs that define what is human”, by once again showing works “questioning the primacy of the human being at a fundamental level”. It is thus stipulated that these observations “enable us to conceive these constructs anew in the form of the inhuman.”11 The choice of this term (which, far from being insignificant, seems arguable here) and its semantic orientation nevertheless remain obscure. Theoretician Rosi Braidotti considers the inhuman behavioural patterns of the 20th and 21st centuries as consequences of the predominance of technology over the construction of the subject in the course of modernity, by making the qualification—quoting J.F. Lyotard’s L’Inhumain (1988)—that the inhuman “functions as the site of ultimate resistance by humanity itself against the dehumanizing effects of technology-driven capitalism. In this respect the inhuman has a productive ethical and political force […].”12 The position taken by the exhibition seems to be more inclined towards Lyotard vision, opting for a positive way of looking at a humanity taking its future in hand. But on the other hand the works tend towards a future which may turn out to be cruelly disastrous for human beings. Stewart Uoo displays the brutality which we might be confronted with in our relations with the other, with the series Security Window Grill (2014). These sculptures consist of security grills normally affixed to home windows, partly covered with silicon and human hair, pointing to the trace of the unfortunate passage of a body trying to go beyond, leaving behind repellent strips of flesh. The disintegrated human body and the dispossession of the self in favour of meta-organizations with coercive and profit-oriented goals also inform most of the works exhibited in “Inhuman”.

Aleksandra Domanović, HeLa on Zhora’s coat, 2015, flatbed print with UV white ink on soft PVC film, polyester yarn, 110 × 100 × 70 cm. « Inhuman », Fridericianum, Kassel, 2015 ; © photo: Achim Hatzius.

With HeLa on Zhora’s Coat (2015), Aleksandra Domanovic is interested in the development of human cells after death, based on the case of Henrietta Lacks. By multiplying at an amazing rate, the cancerous cells of this Black American woman were sampled without her agreement and subsequently gave rise to fruitful therapeutic advances; they are still proliferating, but her heirs have never been able to profit from this. The dispossession of the self, associated with post-mortem life, has its digital counterpart in the social networks, as is demonstrated by Cécile B. Evans with Hyperlinks or It Didn’t Happen (2014), a video probing the development and circulation of images/information, once the Internet users have passed away. Melanie Gilligan’s mini-series titled The Common Sense (2014-15) depicts a society that has replaced oral and gestural communication with others by an immediate sharing of physical and emotional sensations. Far from realizing the dream of a more altruistic and empathetic society, the “patch” permitting this new type of communication in the end only helps to nurture strategies of capitalist optimization and efficiency, while at the same time scaling back everyone’s private life. A world which strangely conjures up our own, in which the “patch” has Facebook and smartphones as equivalents…

Johannes Paul Raether, Cave of Reproductive Futures, 2015. « Inhuman », Fridericianum, Kassel, 2015 ; © photo: Achim Hatzius.

In a Brave New World like senario, the performer Johannes Paul Raether incorporates the body of Transformella (one of his many avatars) and advocates the industrialization of human reproduction by way of a “Reprovolution”, taking in vitro fertilization as a given, as well as pre-implantation diagnosis. Because methods of heterosexual reproduction are now being rivalled by other matrices of human reproduction, he invites visitors—at the heart of a sanitized futuristic installation, staked out by strollers taking the shape of insects, titled Cave of Reproductive Futures (2015)—to think about new forms of procreation capable of giving rise to a new type of humanity. In the guise of a projection into the future, “Inhuman” does not go beyond the ideas expressed in “Post Human”, because the exhibition does not show how people might fully participate in a technologically oriented society, without losing their soul and their integrity en route. There, human being is constantly assailed by violence, be it physical or moral. Instead of emphasizing a possible understanding, and a productive and peaceful co-existence between man and his technologically altered environment, “Inhuman” keeps us in a world where human is dispossessed of himself, and replaced.

Juliette Bonneviot, XenoEstrogens, 2015. Vue de l’exposition /Installation view of « Looks », 2015, Institute of Contemporary Arts London (ICA); photo: Mark Blower.

The exhibition “Looks” (2015) at the ICA in London examines the way in which social networks and digital culture are affecting identity, gender, and performance potential, at a time when calling the male-female dualism into question seems to be progressing in human mores. Closely bound up with post-humanity, the destabilization of genders and plurality-based identity (also broached in “Post Human”) blend perfectly with the digital culture where “the body and the expression of its identity are no longer automatically linked”.13 Initially, “Looks” seems to overlap with the identity-related proliferation on-line and off, Monique Wittig’s theories arguing that “there are not two sexes, but as many sexes as there are individuals”, and Judith Butler’s which, in her own way, take up the fact that if the socially admitted gender is a construct calling for performance in order to exist, then every type of sexuality can be constructed and proliferate.14 The works seem to record the significance of this multiplicity, and the freedom to define oneself, over and above any social straitjacket. This has the plus point of making post-humanity more enviable, because it permits everyone to accept themselves the way they feel inwardly. But these works are combined with an angst-inducing presence: is free sexual construction conjugated with digital technologies doomed to degeneration? This is actually what seems to be anticipated by the side-effects of xenoestrogens in Juliette Bonneviot’s monochrome works XenoEstrogens (2015), the panoptico-totalitarian dystopian world depicted in Wu Tsang’s video A Day in the Life of Bliss (2014), and the charred and necrosed cyborg manikins in Stewart Uoo’s Don’t Touch Me (2015), which, as they are, cannot support the benefits of freedom offered to all and sundry to construct/produce their own identity.

Installation view of “ProBio”, part of “Expo 1: New York” at MoMA PS1, 2013 (works by Dina Chang, Josh Kline, DIS and Shanzhai Biennial). © MoMA PS1; photo: Matthew Septimus.

Through the works on view, these shows amalgamate post-humanism with trans-humanism, and catastrophism, by associating it with post-apocalyptic visions, and visions of self-loss, while at the same time perpetuating the belief in a purely teleological decline of the humankind. It is thus possible to reproach these projects for not embracing pragmatism and losing ground in the wake of excessive speculations too imbued with science-fiction literature and films. N. Katherine Hayles, a literary critic specializing in the relations between literature and technology, has furthermore emphasized the role of this literary genre in the dissemination of cybernetics in an intelligible form among a wider audience.15 This popular culture has, over time, propped up this one-sided vision of post-humanism based essentially on fear, anxiety, and the end. If we can be in no doubt that present human and non-human conditions, wherever they may be on Earth, are worrying, it is also worth to describe the critical theories of a post-humanist school of thought,16 persuaded that the post-human future of humanity can be broached in a positive and politically creative manner. In 1991, Donna Haraway imagined the “cyborg” (a metaphor for a new humanity) as a constructive alternative to the racist, homophobic and anthropocentric humanism then reigning, specifically because the “cyborg” has no origin, it is rootless and free to re-invent itself at will in the wake of criticism, and thus improve the human condition: “a cyborg world might be about lived socially and bodily realities in which people are not afraid of their joint with animals and machines, not afraid of permanently partial identities and contradictory standpoints”.17 N.K. Hayles perceives in post-humanism “the exhilarating prospect of getting out of some of the old boxes and opening up new ways of thinking about what being human means”. Reacting to the anxiety caused by post-humanism, she puts forward the notion that “although some current versions of the post-human point toward the antihuman and the apocalyptic, we can craft others that will be conducive to the long-range survival of human and of the other life-forms, biological and artificial, with whom we share the planet and ourselves.” She maintains that “to conceptualize the human in these terms is not to imperil human survival but is precisely to enhance it, for the more we understand the flexible, adaptive structures that coordinate our environments, the better we can fashion images of ourselves that accurately reflect the complex interplays that ultimately make the entire world one system”. She thus wishes to defend a version of “posthumanism that embraces the possibilities of information technologies without being seduced by fantasies of unlimited power and disembodied immortality, that recognizes and celebrates finitude as a condition of human being […].”18 Because, according to her thesis, the presence of the body, or embodiment, is inevitable in a cybernetic world, the post-human future cannot therefore encompass any threat calling the human body useless. In addition, the development of a “new morality” advocated in “Post Human” appears in Rosi Braidotti’s work which guarantees that “the ethical imagination is alive and well in posthuman subjects, in the form of ontological relationality. A sustainable ethics for non-unitary subjects rests on an enlarged sense of inter connections between self and others, including the non-human or “earth “others, by removing the obstacle of self-centered individualism on the one hand and the barriers of negativity on the other”.19

J. Deitch predicted seeing artists involved not only in redefining art, but also in redefining life.20 The link between art and life, already tentatively made in the 1970s, then ousted by the extreme individualism of the 1980s, thus seemed illusory for the art of the 1990s, despite new attempts aimed in that direction. If this redefinition of life in the age of the post-human lies indeed at the heart of the theories of D. Haraway, N.K. Hayles, and R. Braidotti − among others not mentioned here −, it does not appear in the exhibitions examined above. Nor in the latest Taipei Biennial The Great Acceleration (2014) at which Nicolas Bourriaud could merely note “a possible global refoundation of aesthetics”,21 otherwise put a “redefinition of art” to use J.Deitch’s words. Redefining art would consist in reproducing the sempiternal linear plan in which one aesthetics, one movement, and one –ism comes after another, which no longer has its place in a context of multipolar creation, at once too complex and on the move to be defined. But we are also entitled to wonder why redefining life should fall to artists. If the art of our post-human world cannot be defined, and if redefining life is presented as a huge task for artists, it would be preferable for exhibitions having post-humanity as their theme to become, rather, the ground for a constructive and positive line of thinking, stripped of all fear about our existence in an ever more exaggerated technological environment.

1 Post Human, exhibition catalogue, Deste Foundation of Contemporary Art, Athens ; FAE, musée d’Art contemporain, Pully-Lausanne ; Castello di Rivoli, Turin ; Deichtorhallen, Hambourg, FAE, Pully, 1992, 152 p.

2“This new interest in the figure is, however, not to be found where it would traditionally be expected, in painting and in conventional sculpture. The new interest in figuration, in keeping with the social and technological trends that are inspiring it, is conceptual rather than formal. The new figurative art is emerging through the channel of the conceptual-body, and performance art of the late ‘60s and ‘70s rather than through the figurative-painting tradition”, in Post Human, op. cit., p. 42.

3 In addition to the exhibitions analyzed here, let us mention “ Post-body Projections”, 0gms gallery, Sofia (2013) ; “The New Humanists: Hybrids in Purgatory”, Autocenter, Berlin ; “Human/Evolution/Machine”, Galerie Hussenot, Paris ; “Humainnonhumain”, Fondation d’entreprise Ricard, Paris (2014) ; “Digital Conditions” Kunstverein, Hanover ; “Real Humans”, Kunsthalle, Düsseldorf (2015) and “The New Human, Knock, Knock, Is Anyone Home?”, Moderna Museet, Malmö (upcoming in February 2016).

4 I. Hassan, “Prometheus as Performer: Toward a Posthumanist Culture ?” in Performance in Postmodern Culture, edited by M. Benamou and C. Caramello, Coda Press, Madison, 1977, p. 212.

5 Op. cit., p. 214.

6 Post Human, op. cit., p. 39 and 47.

7 Post-Internet Survival Guide, edited by par Katja Novitskova, Revolver Publishing, Berlin, 2011, p. 4.

8 http://www.momaps1.org/expo1/module/probio/

9 http://www.frieze.com/issue/article/focus-interview-josh-kline/

10 “From the perspective of the present, the future of humanity might be monstrous… but this is not necessarily a bad thing”, extract from the video Stealing one’s own corpse (2014) by Julieta Aranda, quoted in Inhuman’s statement. http://www.fridericianum.org/exhibitions/inhuman

11 http://www.fridericianum.org/exhibitions/inhuman

12 R. Braidotti, The Posthuman, Polity Press, Cambridge, 2013, p. 109.

13 https://www.ica.org.uk/whats-on/seasons/looks

14 J. Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, Routledge, 1990.

15 N. K. Hayles, How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature and Informatics, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1999, p. 20-24.

16 This school of thought is nevertheless known to the curators of these exhibitions.

17 D. Haraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto. Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century”, in Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, Routledge, New York, 1991, p. 295.

18 N. K. Hayles, How We Became Posthuman, op. cit., p. 285, 291, 290 and 5.

19 R. Braidotti, The Posthuman, op. cit., p. 190.

20 Post Human, op. cit., p. 47.

21 http://www.taipeibiennial2014.org/index.php/en/

(Image on top: Wu Tsang, A Day in the Life of Bliss, 2014. « Looks », 2015, ICA, London. Photo: Mark Blower)

- From the issue: 75

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Everybody in the place. Clubbing as an antidote to the contemporary art institution?, Protective Body,

Related articles

Some white on the map

by Guillaume Gesvret

Toucher l’insensé

by Juliette Belleret

An exploration of Cnap’s recent acquisitions

by Vanessa Morisset