Poetry is dead, long live poetry!

Performance and poetry

When we talk about “sashays”1, systems, literature beyond books2 and neo-literature,3 a new paradigm of poetic creation is being ushered in today in the world of contemporary art, one which makes the letters leap out from the page beyond the text. This hold-up by artists of a medium traditionally associated with the book, and above all the page, is becoming a phenomenon of some magnitude, endorsing the age-old interferences of art and literature, and the visual and the verbal, be it readable or audible. The porous nature of the various disciplines, resulting from the different breaks which the 20th century and its different avant-gardes saw succeeding one another, gives rise to practices leading to a certain indistinctness between poets and artists: the fact that artists write and poets are invited to museums puts into some perspective the already weakened distinction between the arts as well as the separatist tradition that goes hand-in-hand with it. Poetic creation is in effect benefitting from a new form of media attention and is becoming plural, as it is translated in different media, no longer restricted to the book: poetry is visual, digital and sonic, it is performance. This latter is especially interesting because it introduces a vitalization of literature by way of its in praesentia production. While in different recent installations—in particular those produced by Ed Atkins, Happy Birthday!!!, at the City of Paris Museum of Modern Art, and the Julien Prévieux show, “Mordre la Machine”, at the [mac] in Marseille—the body is done away with in favour of dehumanized installations depicting, with anxiety or cynicism, the importance of technologies in our lives, these poetic practices, from public readings to performance as such, are part of the contemporary brouhaha4 or hubbub, by re-investing literature with its logical systems involving proliferation, in the host of public spaces. This situation stems from a long history, condensing two distinct but parallel contributions, which it might be useful to describe in broad brushstrokes in order to shed light on a present-day scene which is prolific and exciting, and on a visual and performative future development of poetry.

“Art and life intermingled”: performance and experimental poetry

The exile of Americans after the Second World War encouraged the introduction of new art forms, in the tradition of the Dadaist experiments which flourished in cabarets in the mid-1910s. But it was in the 1930s, at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, that the initial tests took place. Many artists, soon to be members of the neo-avant-garde, became involved in a reconfiguration of the poetic act, among them John Cage, Merce Cunningham, and Robert Rauschenberg, up until the ‘events’ organized in 1952. Allan Kaprow subsequently ushered in the notion of ‘happening’. Rejecting the traditional idea of art, what was then involved was incorporating artistic and creative forms within the daily round. Artistic changes are the consequence of an increased awareness of the need to alter experience and modify everyone’s relation to art, while not being limited to an aesthetic dimension: they thus result from a philosophical bias. In an essential text which retraces this development, Jean de Loisy, who curated the exhibition “Hors limites. L’art et la vie, 1952-1994”, brings together different creative methods in this conception of art, methods such as “Action, sonic poetry, combine-paintings, events, happenings, assemblage, environment, de-collage, intermedia, leap into the void, monotone music, filmless cinema, 4’33” of silence, free jazz, beat generation, lettrism, trap-picture, situationism, Gutai, New Realism, neo-Dada, Living Theatre, Fluxus…”.5

A whole host of new art practices was being developed at the same time in three different continents: in the United States, in western Europe, and in Japan. The prospect of connecting art to life through the body, the environment, and time and space, made possible by the performance, seemed to be the way of countering the apolitical nature of the then predominant abstract expressionism movement. There thus appeared a desire to appropriate the stage by turning the artistic gesture, no matter how ephemeral it might be, into the work as such. Present work, with uncertain remnants—artists can leave “imprints”,6 remnants of their performances, but not in a systematic way. In Europe there unfolded a myriad events, in particular thanks to the intercession of Jean-Jacques Lebel who, in 1962, organized the Fluxus week at the American Center in Paris. Likewise, the first Domaine Poétique event was held at the Le Fleuve bookshop-cum-gallery, brainchild of Jean-Clarence Lambert, bringing together, inter alios, François Dufrêne, Robert Filliou, Ghérasim Luca, Jean-Loup Philippe and Emmett Williams. It was followed by many other evenings involving Fluxus artists, New Realists, one or two lettrists, and Americans associated with the Beat Generation, including William Burroughs and Brion Gysin. It was also at that particular moment that Bernard Heidsieck was developing his “action poetry”, and Henri Chopin his “sonic poetry”. Another Lebel brainchild, Polyphonix, an International Festival of live poetry, was founded in 1979, like a laboratory for the most hybrid of poetic experiments.

The poetic performance finds its way into art centres and festivals

The extension of these practices into the present-day artistic field illustrates a palpable and obvious energy in all sorts of museums, art galleries, foundations and theatres. Festivals, be they in Paris or Marseille, give pride of place to the poetic performance, whose institutional effervescence attests to its rootedness in a certain contemporary art heritage. For its second event, in September 2018, the Festival Extra! organized by Jean-Max Colard at the Centre Pompidou, appears like a space where literature leaves the book in order to display itself and be heard, as well as being felt, and talked about. Different literary forms were represented, from visual poetry to readings and performance. This latter was presented in many different ways, and in particular in its closeness to slam and music. The approach adopted by the American artist Tracy Morris incidentally incarnates this orientation, mixing the input from the popular culture of live shows and the experimental legacy of sonic poetry. She who defines herself as an artist of the page nevertheless involves herself, body and voice, in a performance aptly titled Sound off the Page, with vocal experiments akin to jazz sounds and based on a poetics subtly speaking out against racial discrimination.

Jérôme Game is altogether different. An old hand in art circles, who even devised, for the inauguration of the Louis Vuitton Foundation, the programme Poésie Now!, devoted, it just so happens, to many different forms of poetry, reading, and performance, he proposes an intermedia performance with a mixture of text, voice and video. Around the World 3.0. thus records, based on a montage of many different materials taken from YouTube, with which the poet interacts, a paradoxically motionless journey, illustrating the ceaseless flux of the contemporary. The concertinaing between body and digital medium creates a jerky rhythm and the oscillation of the media shows the creative instability of the performance which is updated in the determined and defined space of the here and now, henceforth getting away from the book, once and for all.

The Festival Extra! also, since its creation last year, awards the Bernard Heidsieck prize. Chaired this year by Julien Blaine, the jury rewarded the Swedish artist Fia Backström, Michèle Métail having for her part received the prize of honour hailing her pioneering, hybrid and multi-cultural work, in the field of experimental poetry.7 As a partner in the event, the Fondazione Bonotto also awarded a prize to Alain Arias-Misson.

As an older fixture in the French and international art scene, Actoral was held in Marseille, from September to October 2018, for its 18th event. The festival founded by Hubert Colas encompasses a myriad cultural venues, in particular La Friche la Belle de Mai, the [mac], the Montévidéo art centre, the Mucem, and different theatres, bookshops and galleries. The event proposes a broad programme of contemporary work: visual arts, theatre, dance, music, literarature and, needless to say, performance. In this sense, there are also different artists programmed at the Centre Pompidou, such as Benoît Toqué with Entartête, and the project of Frédéric Boyer and Violaine Lochu, Rappeler, boosted by the Poésie Plate-forme unit of the Fondation d’entreprise Ricard.

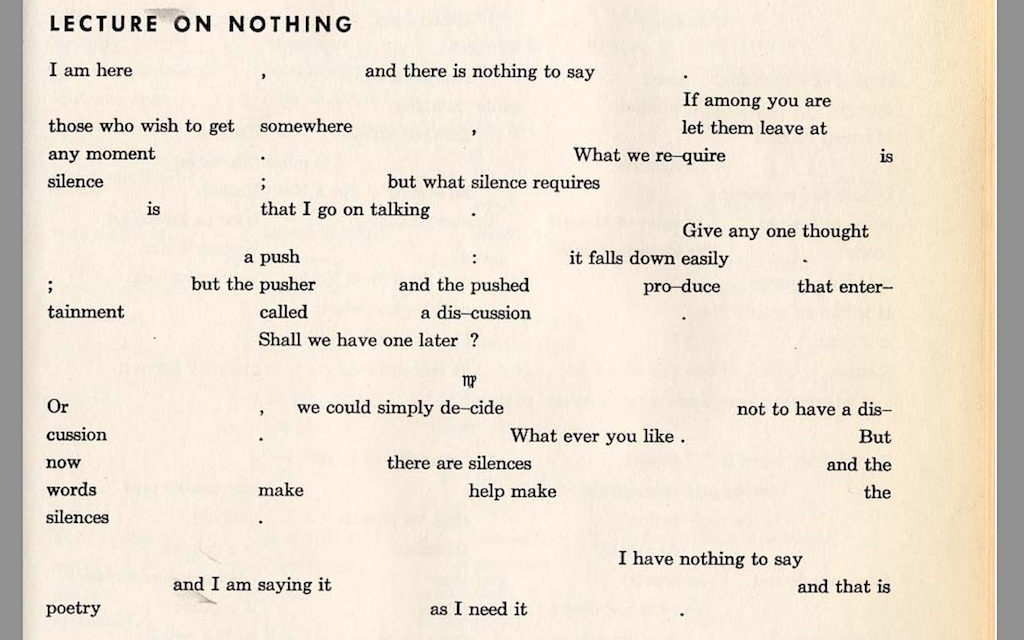

Held at the Mucem, the adaptation of John Cage’s Lecture on Nothing reveals another kind of performance and unveils the malleability of the original text, to the point where a choreographer appropriates it. Jérôme Bel presents a minimalist set for it, targeted at the performer and his body. This voiding of danced language tends in fact to put a reflexive praxis at the centre of the work, which is here given concrete form in a proposed interpretation of Cage’s piece. Presented in 1949 in New York, Lecture on Nothing was offered as a composition where the text borrows the composer’s musical formulations and develops the artist’s aesthetic, philosophical and ethical thinking. Structured by many repetitions and marked by silences, evoking both geography and pleasure, art and the difficulty of talking about nothing, the discourse is punctuated by self-referential pauses which pepper it with a certain wit: “I have nothing to say and I am saying it and that is poetry as I need it”. Jérôme Bel organizes his lecture based on an austere set, sitting down, alone, at his table. Traversing decades and presented many times, the score is deciphered at the whim of its slow, throbbing beat, in an interpretation which makes room for the vagaries of the voice and imperfections in pronunciation. As an experimental proposal in its form, what is indeed involved is an experiment which is proposed by the performer, where the contribution of zen philosophy and hypnosis in Cage’s research is obvious.

Another hypnotic experience was the one presented by the winner of the 2017 Bernard Heidsieck prize, Caroline Bergvall. This Franco-Norwegian artist produced Ragdsawn 43o2’ at the Fort Saint-Jean, very close to the Mucem, at daybreak. The setting for the performance, already magnificent, was then rendered spectacular because of the dawn light. Like a bridge between the city’s heritage and the extremely contemporary nature of the work, the first French presentation of this performance overlapped languages and media, and was not confined to the textual discourse: reciting a poetry with many different dialects, Caroline Bergvall invites onlookers to a ritual lasting about an hour in which voice, song and electronic music meet, asserting the obvious “flirt”8 between sonic poetry and electro-acoustic music. As an intimist work, because of its context, it questions the link between individual and collective, which is conveyed by the head-on encounter between the performer, with her modulated and metallic voice, and the opera singer Peyee Chen.

It was in this same appropriation of a patrimonial place in Marseille that Alex Cecchetti situated his performance a few weeks earlier, as part of Paréidolie, the International Contemporary Drawing Fair, echoing his show at the FRAC PACA, “La Chapelle aux cent mille yeux”. The multifaceted artist, invariably witty, proposed Nuovo Mondo at the Vieille Charité, in the historic Le Panier neighbourhood, a stone’s throw from the Mucem. The performance is presented like a seminar on poetry, turning the performer into nothing less than a middleman, henceforth calling to mind certain lecture-performance practices. Inviting visitors to a journey consisting of walking and words, Cecchetti situates his narrative in the Dantean world of Inferno and Paradise, and opens up a highly charged and poetic dialogue with his travellers for an hour. The work thus tangibly engages the spectator in a line of thinking by way of an itinerary somewhere between reality and fiction.

From art centre to roundabout: the alternative circuits of the performance

Over and above institutional events, it is a whole set of places, be they cultural or marginal, which accommodates the performance, as is illustrated in particular by the work of the author Ayizadé Baudoin-Talec, who recently published the anthology Les Ecritures bougées (Editions Mix). What is thus involved is bringing together many texts resulting from events organized by her, in different venues, within the eponymous structure for producing and distributing poetry that she founded. In a multiple relation to literature, congealing things by the written word makes it possible to prolong and document events “trying to identify in contemporary work new and novel forms offering a time, a space, and a particular way of listening to words.” If the novel character turns out to be debatable, the fact still remains that the undertaking has the absolute interest of promoting a vitalization of the present poetic scene. The transposition of the performances towards the book medium is thus endowed with all the potential of the material character of the page, declining text but also typographical and even graphic work relaying the voices of the different artists, poets, performers and also choreographers such as Pierre Alferi, Olivier Cadiot, Thomas Clerc, Joël Hubaut, Arnaud Labelle-Rojoux, Valérie Mréjen, Anna Serra, and Benoît Toqué.

Probably more radical are the performances of certain authors who try to duplicate the public dimension of the format, by using everyday places and refusing to restrict creation to art spaces. In his book La Domestication de l’art. Politique et mécénat (Editions La Fabrique, 2017), Laurent Cauwet, founder of Editions Al Dante, lengthily rails against the institutionalization of originally subversive art praxes, and what he regards as an enslavement of artists, who have become employees of (corporate) foundations; likewise, Nathalie Quintane talks about a “patronage turning-point” in the book she is coordinating with Jean-Pierre Cometti, titled, it just so happens, L’Art et l’argent (Editions Amsterdam, 2917). In this sense, despite its inclusion in the art market, the performance can take part in a distancing operation, in its visual, plastic and hybrid qualities. This is the case, in particular, with Charles Pennequin and his Armée Noire collective which, regardless of an evident recognition by institutions and recurrent participations in recognized cultural places, tries to broaden the already eclectic field of live poetry towards an aesthetic that is more linked to the underground, by working in different social spaces, like the street, bars, and roundabouts, where improvisation is predominant. Similarly, we can pinpoint the protest force which certain poets are trying to associate with performance. Julien Blaine, for example, has been involved since the 1960s with a work which connects aesthetics and politics, up until his recent performance on the Jean Jaurès square in Marseille, during the movement against the re-organization of the La Plaine district.

In a state of perpetual motion, the extension of the poetic domain towards contemporary art should not, however, underwrite a definitive exit from literature. If a fantasy about the “post-literary” phenomenon does inform criticism, to pessimistic ends or, conversely, within the perspective of a recognition and enthusiasm with regard to new forms of creative potential,9 poetic practices, labile and open, are being updated in many different places, and are turning performance into a fully-fledged method of publication. It is up to the public to take it up…

1 See Jean-Marie Gleize, Sorties, Paris, Questions théoriques, coll. “Forbidden beach”, 2009.

2 Olivia Rosenthal and Lionel Ruffel (eds.), Littérature, “La Littérature exposée. Les écritures contemporaines hors du livre”, n° 160, December 2010.

3 Magali Nachtergael, “Le devenir-image de la littérature : peut-on parler de “néo-littérature” ?” in Pascal Mougin (ed.), La Tentation littéraire de l’art contemporain, Dijon, Les presses du réel, 2017.

4 See Lionel Ruffel, Brouhaha : les mondes du contemporain, Paris, Éditions Verdier, 2016.

5 Jean de Loisy, “Bouleversements de situations”, Hors limites. L’art et la vie, 1952-1994, catalogue for the exhibition at the Centre Pompidou, from 9 November 1994 to 23 January 1995, Paris, Centre Georges Pompidou, 1994, p. 14.

6 See Gérard Genette, L’Œuvre de l’art I. Immanence et transcendance, Paris, Seuil, coll. “Poétiques”, 1994, p. 77.

7 Her work has incidentally been the subject of a very recent study edited by Anne-Christine Royère, Michèle Métail, la poésie en trois dimensions, Les presses du réel, 2019.

8 I have borrowed the expression from the title of the playlist of Gaëlle Théval and Anne-Christine Royère devised as a sonic extension of their article “‘Des chemins parallèles n’excluent pas flirts, tendresses, violences et passions’ : poésie sonore et musique électro-acoustique” (Revue des Sciences Humaines, “Poésie et musique”, n°329, 2017). The podcast brings together in particular works of Bernard Heidsieck, Stockhausen, Arthur Petronio, Henri Chopin, François Dufrêne, John Giorno, Anne-James Chaton, Andy Moor & Alva Noto : http://synradio.fr/quelques-flirts-entre-poesie-sonore-et-musique-electro-acoustique-orchestres-par-gaelle-theval-et-anne-christine-royere/

9 See Johan Faerber, Après la littérature. Écrire le contemporain, PUF, August 2018.

Related articles

Paris noir

by Salomé Schlappi

Some white on the map

by Guillaume Gesvret

Toucher l’insensé

by Juliette Belleret