Exposed in AIDS at the Palais de Tokyo : The Living and the Dead at Work

From 16th Feb. to 14th May, 2023

“All those who continued producing artistic forms, to fight against political injustices, against being silenced, as well as against the loss of joy—all forms of joy, whether collective, substance-induced, etc.—provided us with an inheritance by staying alive for as long as possible, creating all the while1.”

In 2017 Elisabeth Lebovici’s What AIDS Did to Me: Art and Activism at the Close of the 20th Century, a largely autobiographic work, was published. This striking essay attempts to untangle the complexity of the relationships between this devastating illness and contemporary artistic production. Here, the HIV epidemic is described in terms of a profound epistemic and paradigmatic rupture—a division that resulted in the destabilization of knowledge and power systems—, which we are still having to contend with today. AIDS can be described as an “epidemic of representation2”, leaving damaged in its wake a great number of artists and actors in the arts. For François Piron, curator at the Palais de Tokyo, this interpretation echoed significantly with his own curatorial research on the marginalisation of alternative art spaces by public institutions, from a voluntarily political angle. In order to prolong the discussion with the author, Piron wished to respond with a dialogue in the form of an exhibition. Together, they question in a variety of ways what it means, to use an expression by William Haver, to live and create, “in AIDS.”

Crédit photo : Aurélien Mole

“Exposed” is far from the sort of manifestation one might expect from an institution which produces and disseminates contemporary art. It cannot be classified as a museological attempt to produce a “retrospective”. Avoiding the pitfalls of hagiography, it refuses to become locked into a mythologisation of the past. Nor is it a militant war machine, as the MUCEM exhibition, “HIV/AIDS: The Epidemic Is Not Over!” has been perceived. Taking Act Up’s slogan as a point of departure, its activism was overtly stated. The Palais de Tokyo’s exhibition takes a different, opposite tack, avoiding any engagement in the cultural conflicts which continue to haunt this topic. The exhibition’s activist stance is directed more toward its ability to open doors to a variety of artistic, ethical and political issues which question the role of the institutional structure, without ignoring the contradictions this entails.

“Exposed” is something entirely different; it is an aesthetic experiment which combines material artefacts with a present-day, emotional narrative. According to Alain Ménil, “The only way to reveal the entire human dimension of AIDS is to connect it with all of the planes of existence it touches upon. The idea is not to make illness into something it is not, but rather to think of it in terms of an experience—individual as well as collective, personal as well as social3. ” Here, the works operate directly from a palette of feelings and lived experiences which speak to the many lost lives, those who survived, and the ensuing guilt, to the feelings of loss and despair, of rage and anger, to the caretaking of others, but above all, to vitality and desire.

“The AIDS crisis is only just beginning.” A barrier bearing this statement hangs above the entrance of the Palais de Tokyo, providing an entry point to the exhibition. This call to arms by artist-activist Gregg Bordowitz clearly indicates the impact the epidemic has had over an extended period of time, and which does not appear to have an endpoint. The central role of text and language is the first point made by the exhibition. The relationship with writing and words manifests itself in the militant communicational and informational materials (posters, flyers, etc.), absorbed in the fight against HIV and in defense of LGBTQ+ causes.

Nonetheless, this relationship between language and creativity does not preclude the appearance of ethical tensions involving the question of freedoms and responsibilities of the author toward the HIV epidemic. In the 1990s, for example, certain HIV-positive homosexual artists (Hervé Guilbert, Cyril Collard, etc.) appeared to be opposed to the overarching mood of political emergency which pervaded most activist milieus. Their practices formed a poetic link between love and the virus, referring to the HIV-positive individual as having a personal and sacrificial destiny. Guillaume Dustan’s sublime literary trilogy, referred to as “autopornographic” raised questions and also anger amongst members of Act Up-Paris. They accused the author of encouraging readers to engage in unprotected sexual activity in the face of the high risks involved at the time. Through the installation My Epidemic (Small Modest Bad Blood Opera), which was exhibited at the 2015 Venice Biennale, Lili Reynaud-Dewar appropriates the conflict between Dustan and Act-Up founder Didier Lestrade, in the form of a sung confrontation. A chorus formed by students of the artist interprets accusations made by the association, while Reynaud-Dewar and Nicolas Murer sing the writer’s response. This work reveals that a political orientation is never a mere abstraction when it comes to the diversity of subjectivities encountered in topics as complex as this illness4.

The experimental filmmaker Yann Beauvais is equally interested in confronting discursive statements. The video installation Tu, sempre (2002-2023) (You, Always), which has been in constant evolution for the past 20 years, is an account of a multitude of reflections revolving around the AIDS theme. The body of the viewer is integrated into an immersive system of mirrors which reflect the video projections. Beauvais uses a variety of “objective” texts culled from journalistic or political analyses, as well as first-person testimonials. This text-based collage technique demonstrates that there is no one, definitive AIDS but rather “multiple AIDS”. The hysterical treatment the epidemic received by American media outlets had previously been evoked in Barbara Hamme’s film Snow Job: The Media Hysteria of AIDS (1989), when fears concerning the illness were at fever pitch.

Established, emerging and marginalised artists alike are all positioned at the crossroads between artistic creation and an epistemology of AIDS. This is visible in the way the exhibition gathers together a heterogeneous selection of material artefacts, textiles, archival materials, photographs, video works and conceptual installations. The works have been grouped together according to aesthetic, formal and intellectual affinities, voluntarily combining different geographical contexts and temporalities. The African collective Bambanani Women’s Group’s Body Maps share a space and dialogue with the Parisian collective Ami·es du Patchwork des Noms’s Patchwork n°21 (2017); each attempts to draw attention to the impact the epidemic has had in different localities. Another example can be found in the pairing of artists Julien Devemy and Régis Samba-Kounzi, who met through their activist activities. Between subjectivity and collectivity, they evoke the questions of homosexuality and Pan-Africanism, as well as notions of race and of class which were inherited through colonialism. The HIV epidemic is a tragic confirmation of the inequalities which exist between the West and the rest of the world.

The recent re-evaluation of HIV as zoonotic, or an epidemic which arises due to imbalances in ecosystems, and the impact the COVID-19 pandemic had on the context of the conception of the exhibition, led to a necessary reassessment. The relationship between the production of artistic objects and the organisation of cultural events along with the considerable amount of waste this engenders is now becoming problematic. Jesse Darling addresses this from a critical standpoint where art historical references dialogue with current political events. For “Exposed”, the artist has produced two transparent vitrines filled with the residue from emblematic works by Félix González-Torres, sourced following their installation at the Bourse du Commerce. While clearly meant as an homage to the American artist who died due to issues related to the illness, the work also launches a debate as to what becomes of these artefacts once the exhibition comes to an end.

Crédit photo : Aurélien Mole

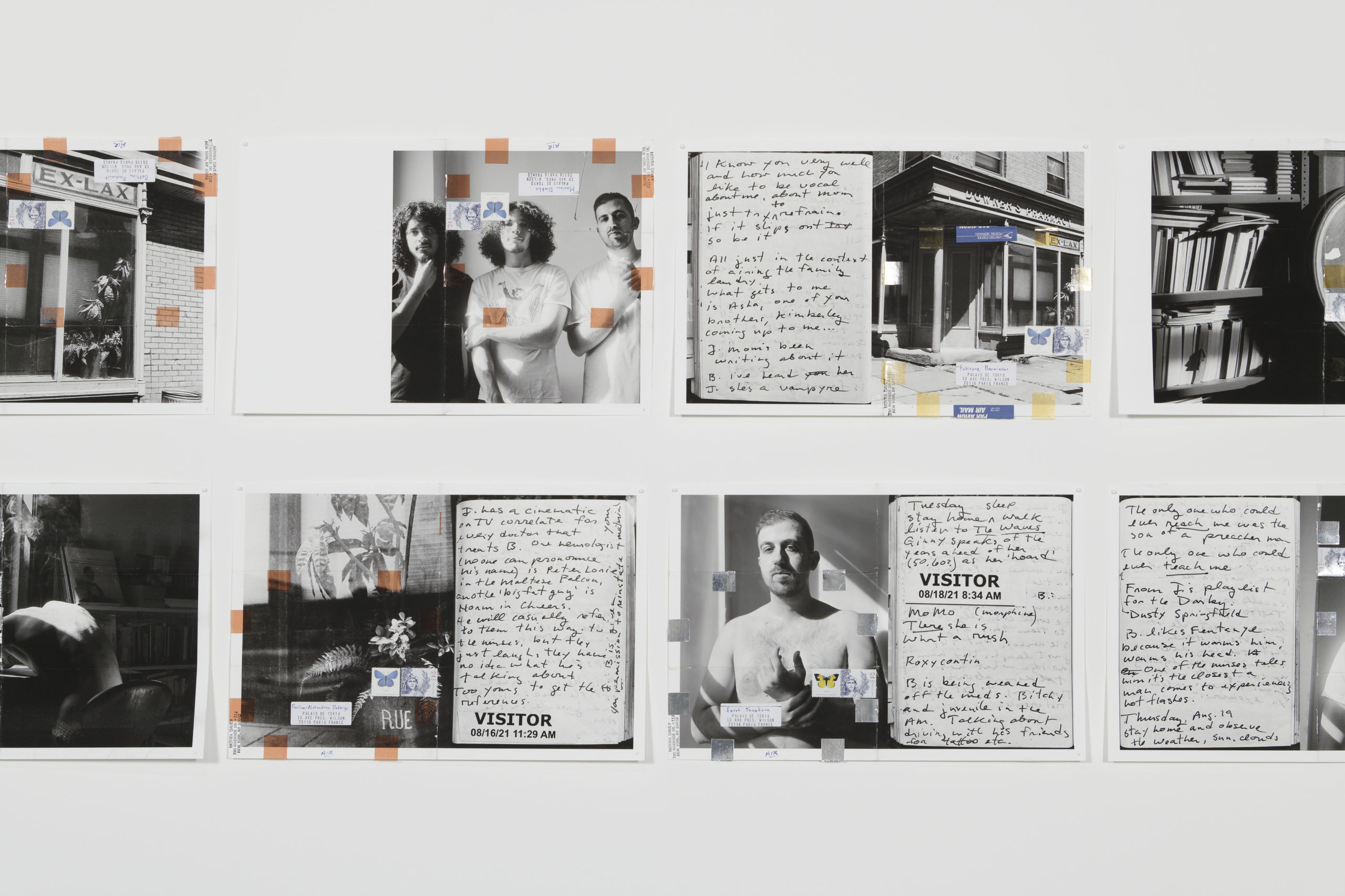

Through an incredibly lively and vibrant dialogue, pride of place is given directly to deceased creators by the living artists who summon them5. To update is to accept the melancholy that provides a present-day testimony to a past which does not pass away, by providing a presence for its ghosts and its traces. The photographer Moyra Davey selected a series of photographs taken by the writer Hervé Guibert. These images are often filled, as in Table de travail, mammouths, homme blessé (s.d.), (Work Table, Mammoths, Injured Man), with manuscripts, typewriters or books. Moyra Davey produced the series, “Visitor” for the exhibition in response to Guibert’s photos, evoking the U.S. health care system. She experiments with the interlacing of photographic images and autobiographical references. Beginning in the 1990s, Félix González-Torres began addressing the questions of transmission and heritage in his “Portraits”, connecting mutually isolated images with minimalist syntax. The works appear as an alignment of words, of dates, of spaces left deliberately vacant on a picture rail. The information given commemorates significant events which are related to the life of a model which changes each time. A feeling of impending loss is therefore already built into its conceptual model.

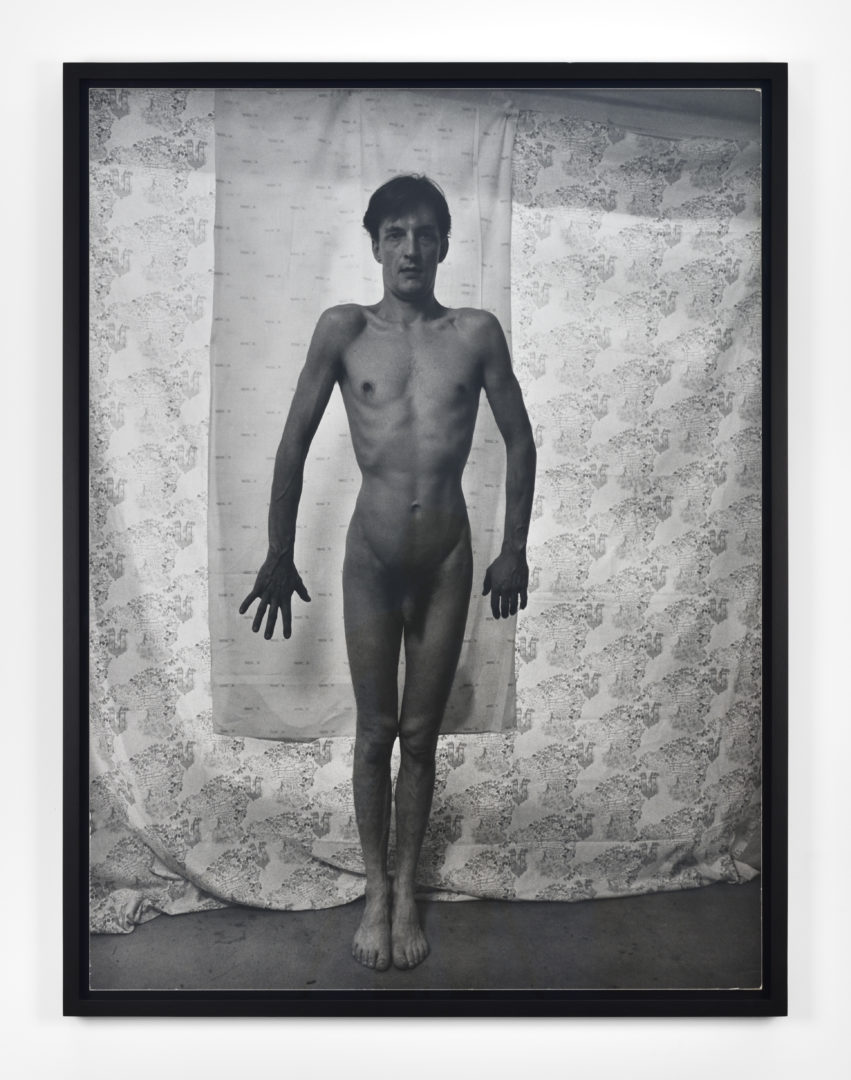

François Piron has also invited friends of the deceased artists, many who were direct or indirect collaborators, to contribute by providing testimonies. The photographer Jean-Luc Moulène documented the actions which make up Rituel de transmutation du corps souffrant au corps transfiguré (1993-1995) (Transmutation Ritual of a Suffering Body to a Transfigured Body) by Michel Journiac. During the beginning stages of the epidemic, the body artist reactivated and updated his performances from the 1970s. The ritual, which was inspired by a liturgical vocabulary, became in this new context a structural element for grieving communities. Following the successive deaths of members of Journiac’s circle, the grieving artist revisited a nude portrait of his deceased friend, the artist Frédéric Nika (known as Darek), originally taken by Moulène, in order to produce an icon. This “phantom image”, to use Guilbert’s expression, was made from gold leaf and the artist’s blood. An incredibly spectral force emanates from the confrontation of these two portrayals. This effect is in part due to the direct and implied representation of the vulnerability and inertia of this since deceased body. Darek’s first name, initial and date of death also feature in Journiac’s Mur des amis morts (1993) (Wall of Dead Friends), an homage to the artist’s dead friends which appears next to those of Gilles Dusein6. Dusein was the founder of the urban pop-up gallery Urbi et Orbi, as well as an important figure in the Parisian art and AIDS activism scene. He was the first to introduce Parisian audiences to the photographic work of Nan Goldin, and regularly modeled for her until his last breath. The filmmaker Marion Scemama’s contributes an emotional account of a collaboration with her deceased friend, artist David Wojnarowicz. In When I put my hand on your body (1989), the filmmaker captures Wojnarowicz in the midst of a sublime scene of homosexual union—a mouth tenderly kissing a lover’s body, caressing their skin. Together, they hold the encroaching presence of death prevalent at the time at bay by giving desire and sensuality in couplehood a central role, “It was as if the light of death could illuminate the darkness of life7. ”

The exhibition’s most powerful section is without a doubt “Fluid Traffic.” Here, a parallel is formed between two struggles subversive queer activism is faced with: the fight against AIDS and another against heteronormative forms and discourses. The constellation of artists and artworks and the display methods used in the space combine to create a singular atmosphere. Philippe Thomas’s enigmatic Parcelle à céder (Lot For Sale)—30m2 of floating flooring lain haphazardly across the Palais de Tokyo’s floor—is the incarnation of the disconnect between the institutional, normative space of the White Cube and claims to a marginal position, which muddies the waters of this discourse. The artist Henrik Oleson gathers together a variety of older and recent works which address in an ironic fashion the relationship between the body, sexuality and social and political norms. The series “Milk” is composed of sculpted resin milk cartons which appear to be filled with unidentifiable body fluids. The video Le corps sous la peau est une usine surchauffée (2005) (The Body Underneath the Skin is an Overheated Factory), in reference to Antonin Artaud, revisits the theme of the injunction made on the body by the neoliberal ideology of cleanliness. Echoes of this can be seen in the video Montre + Lèvre (Watch + Lip) by Guillaume Dustan. The video is an amateur recording of a performance by Christophe Chemin at a Parisian gallery, during a particularly intense period of depression. This becomes evident through the fragments of conversation overheard on the audio track, “I’m so paranoid it’s scary.” Bodies are barely visible here, since Dunstan’s attention was focused mainly on the floor, an aspect that connects superbly with the Phillippe Thomas piece, as well as with the homoerotic, pornographic paintings of the Bastille, which are also displayed here, provoking what Henrik Olesen refers to with delectation as “Queer traffic8 . ”

These works respond therefore, each through their own subjectivity, to a specific political issue, giving access to feelings and methods to fight against the most dramatic effects of the AIDS epidemic on the personal. As explained by Elisabeth Lebovici, the term ‘exhibition’ plays on its polysemic nature at the Palais de Tokyo. The word denotes ‘the act of putting something on display’, ‘the act of giving visibility to something’, as well as ‘the submission of something to an act’. This submission of subjects is all the more relevant given the pandemic context of COVID-19 and the bio-security measures authorities imposed on us all: prohibition of all bodily contact, the isolation of ailing bodies. “Exposed” avoids being categorised as a simple commemorative enterprise. Its hybridity makes it difficult to define with its curatorial, discursive, aesthetic and political turns. The exhibition successfully sheds light on the emotional and sensorial impact contemporary practices leave, through an openness to the outside world, to the individual, to society. The moving dialogues between living and deceased artists are a case in point. “Exposed” is overflowing with an incredible vitality, encouraging the living to put “the dead to work9 .”

______________________________________________________________________________

1 Interview with Vinciane Despret, Exposées (D’après Ce que le sida m’a fait d’Elisabeth Lebovici), Palais de Tokyo, 16th February – 14th Mai 2023, Elisabeth Lebovici & François Piron (dir.), Arles : Actes Sud, 2022, p. 175.

2 Elisabeth Lebovici, Ce que le sida m’a fait, Paris : Jrp/editions / Fondation Antoine de Galbert, 2021, p. 9.

3 Alain Ménil, Sain(t) et saufs. Sida : une épidémie de l’interprétation, Paris : Les Belles Lettres, 1997, p. 128.

4 « Those who criticise Hervé [Guilbert] for the way he talks about AIDS disagree with the way he considers his as his destiny. He didn’t welcome it with open arms but he made the best of his situation. And he died from it. », Mathieu Lindon, Hervelino, Paris : P. O. L., coll. Folio, 2021, p. 94.

5 The magnificent paintings of British artist Derek Jarman will unfortunately not be discussed in this text. For more on this topic, see Guillaume Lasserre’s article in n° 102 of 02 : https://www.zerodeux.fr/en/reviews-en/dereck-jarman-2/

6 Cf. Antoine Idier, Purity and Impurity In Art. Michel Journiac and AIDS, Aurillac : Sombres torrents, 2019.

7 Extract of a conversation between Sylvère Lotringer and Marion Scemama de 2004, printed in the catalogue. Op. cit. p. 118.

8 Ibid., p. 238.

9 Vinciane Despret, The Dead at Work, Paris : La Découverte, 2023.

Head image : Exhibition view, Exposé·es, Moyra Davey – Palais de Tokyo (17/02/2023 – 14/05/2023)

Crédit photo : Aurélien Mole

Related articles

Paris noir

by Salomé Schlappi

Some white on the map

by Guillaume Gesvret

Toucher l’insensé

by Juliette Belleret