Are We All Migrants?

Should artists react ‘aesthetically’ to society’s ills? Should they utter words that differ from those of the media and the ‘politicians’? Or should they decide to be just a sounding board, aware of their powerlessness to act in the face of the global phenomena which regularly assail the world? The migration issue merely extends this old surface antagonism, re-awakening the extinct volcano of militant art, and giving rise to formal stances which are not always felicitous. If the question of the ‘situation’ of art has been exercising cultural circles for more or less a century, its insertion in the political arena seems to have been abandoned, or at the very least the link between art and the transformation of society which was the driving force behind the avant-gardes. When these latter turned their back on wanting to take action on the world—the Situationist critique (Situationism being regarded, wrongly or rightly, as the last of the avant-gardes) refusing the idea that art is at the service of the revolution but rather that this latter, conversely, should be used for the poeticization of life1—the end result was both to render null and void any vague desire for involvement, in the classic sense, and to remove from contemporary art all political content which is not rendered metaphorical or euphemistic; it would however seem that these two forms of human activity are lastingly condemned to maintain chaotic relations, though without being able to give up all manner of overlap. If the extreme fetishism of the work of art causes it to sidestep the aesthetic flattening of the mass-consumer product, this does not in this respect stop the empathetic activities of the struggle taking part in this fetishization. Quite to the contrary: henceforth it is no longer so much a matter of reifying/mythicizing the rare moments of history when art has marched in step with the revolution, but rather of considering that the work is fuelled by these frictions between the argument of emancipation and the assumption of the modern goods to whose latest innovations it greedily aspires, where forms of matter and technologies alike are concerned. There is not really any contradiction between art and politics, as we are told by the philosopher Claude Amey: the two spheres stimulate one another, attract and repel each other, and enter into ongoing negotiation.2 Works as diverse as those of Walid Raad, Jimmy Durham, David Hammons, Jeremy Deller, Omer Fast and Claire Fontaine are the best illustration of this.

The Dross of Colonialism

The two issues exercising the media world at this year’s end are climate change and migrants (or refugees). As much as the first theme has a host of programmes converging on it, stimulated by the COP21 (Conference of Parties/UN climate change conference), held in Paris in early December, announcing itself as a top priority meeting place to discuss the planet’s future, so the second issue appears not to be giving rise to any top-notch art event. Perhaps the absence of any deadline is working precisely against it, while ‘climate’ gives rise to regular meetings in turn spawning as many paroxysmal movements; perhaps, too, the staging of the argument of a (clear) ecological conscience is passing by way of potentially sexier aesthetics than the second, migrant theme, seeming to be bound to be inevitably resolved in documentary form. The fact still remains that language has a decisive place in the treatment which artists are applying to migratory phenomena. Language is neither innocent, nor exempt from consequences: it is potentially discriminatory, creates forms of enslavement, and introduces power plays. Depending on whether one talks about migrants or refugees, we establish radically different categories. For some, the term ‘migrants’ is from now on loaded with disparaging connotations, while the use of the term ‘refugee’ is much more positive. This is why certain media, like Al Jazeera, have decided from now on to use only the word refugee, because the word migrant, according to the Qatar-based TV channel, does not reflect the intensity of the distress, and fails to describe the dramatic situations which candidates for exile have to cope with in order to flee hostile governments, whatever the reasons pushing these people to emigrate: talking of refugees instead of migrants is to shatter a discrimination inscribed in the very stuff of language.3 The semantic debate is in fact bringing to the surface a whole stack of prejudices, like the one involving a disengagement with regard to the local political situations of migrants, when refugees would be more worthy of benefitting from the support of host countries: language thus becomes the agent of a pernicious polarization. On the other hand, the ‘dominant’ language never makes any mention of ‘migration’ from the rich countries to the poor, because the problem of crossing borders rarely crops up for westerners, who are free to pass through any kind of check point, for whatever reason that might suit them, be it economic or as a tourist: pinpointing this reality also sheds light on the duplicity of language and the orientation it leads to.

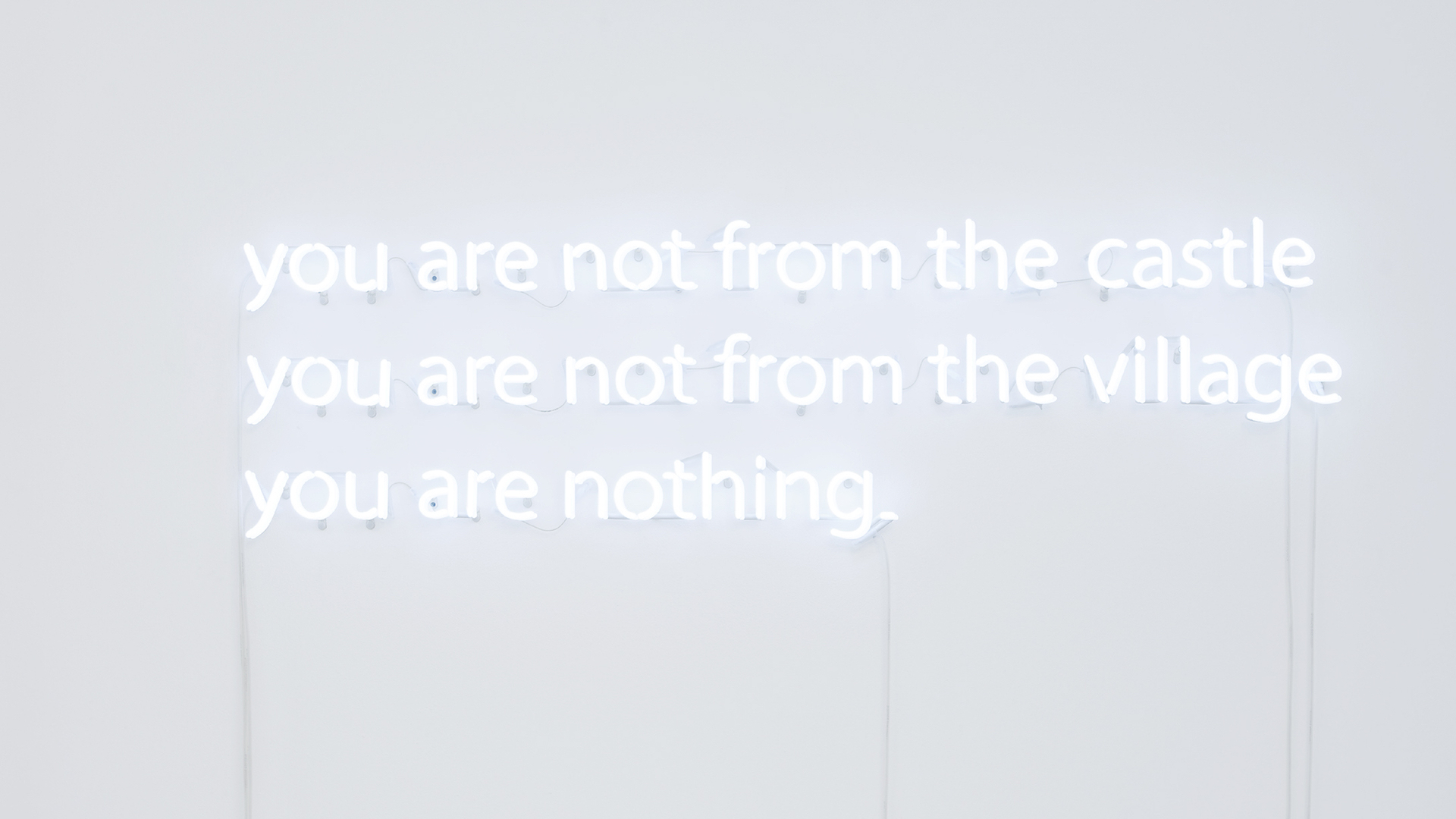

Claire Fontaine, Foreigners Everywhere. Installation view, La Bouilladisse, 19 Sep.-30 Nov 2013

© All rights reserved. Courtesy Claire Fontaine ; Air de Paris, Paris.

Claire Fontaine, Foreigners Everywhere, Nuit Blanche, Belleville, Paris, Oct. 2010. Photo: Florian Kleinefenn. Courtesy Claire Fontaine ; Air de Paris, Paris.

It is when artists use words that they seem to us to be acting in the most effective way to signify the power of language which Bruno Latour talks about:4 Claire Fontaine’s multilingual neon piece, Foreigners Everywhere—like the common-or-garden neon of a local shop—sheds light both figuratively and literally on the propensity of all human beings to represent the figure of otherness, behind the paranoid slogan which the spokesperson of any old extreme rightwing party might easily lay claim to. The declension in all the Earth’s tongues of this piece displays the eminently reversible potential of the formula and, just as we might remember the fearsome responsibility contained in the choice of words, the latter are capable, depending on whether you read them in this light or that, of summoning up completely different feelings and ways of looking at things. The fact that this piece gets far more to grips with the terrible current state of the ‘migratory crisis’ than any other appropriate work merely confirms the irrelevance of these latter when it comes to responding to the present state of political affairs: it is because it is timeless that it best describes the present; it is because it utters an indisputable truth that it exists as a ‘political’ piece; it is because it is ambiguous, like any extreme political slogan, that it works. The territorial aberration resulting from colonial carving-up is producing its effects over time, spreading slowly across the more and more porous frontiers of populations which are prisoners of these boundaries and lines, whose artificiality jumps out at any novice cartographer. But the basic ‘foreignness’ of each human being, which we perforce see as worrying in these times of introspection, is also what underwrites our humanity, well beyond the absurd and passing boundaries of concrete enclosures. For as the piece proclaims, foreigners are everywhere and no fence can ‘protect’ us from them. Claire Fontaine’s words act like a double bind, a paradoxical injunction, with the affirmative momentum cancelling the deceptive statement: at the same time as it seems to cling to this reality by displaying it with all the dazzle of its brilliance, in the same motion it laments it, like an oxymoron set in the heart of the word and the light system, at once clamouring for this reality, and then clamouring against it… In a similar chord, another of her pieces, You are not from the Castle, emphasizes the significance of the linguistic injunction by borrowing a quotation taken from Kafka’s The Castle, which also seems to be timeless, pinpointing the idea that this fear of foreigners refers to archaic patterns of behaviour and tribal reflexes. The sense of encirclement goes hand-in-hand with the threat represented by the foreigner, synonymous with potential danger going back to the construction of the first towns and cities, and the first fortifications by means of which it was necessary to protect against the raids of pillagers and invaders: this also possibly explains why the foreigner is invariably regarded as “one too many, one who always bothers. A trouble-maker”, as the quotation from which Claire Fontaine’s words are taken specifies.

Claire Fontaine, Foreigners Everywhere.

Vue d’installation / Installation view,

La Bouilladisse,

19 Sept. – 30 Nov. 2013

© All rights reserved Courtesy Claire Fontaine ; Air de Paris, Paris.

Claire Fontaine, Foreigners Everywhere, Nuit Blanche, Belleville, Paris, Oct. 2010. Photo: Florian Kleinefenn. Courtesy Claire Fontaine ; Air de Paris, Paris.

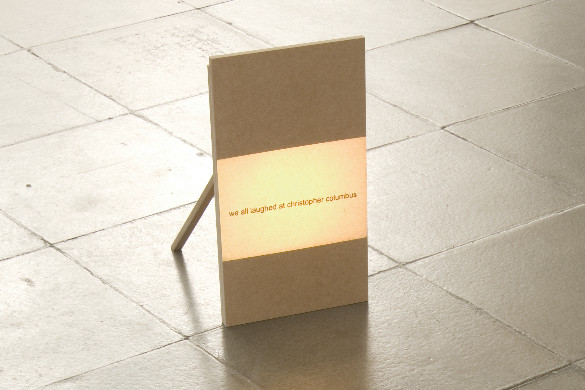

Language also lies at the heart of Runo Lagomarsino’s work, through the still not very widespread concept of ‘coloniality’, which dissects the way in which Eurocentrism has worked its way into the South American continent. Coloniality describes the phenomena whereby the settler culture is imposed to the detriment of that of indigenous populations: it is through language that the so-called superiority of European cultures–mainly Spanish–is lastingly introduced, by way of these latters’ ‘naturalization’ phenomena. One of the most interesting themes dealt with by this concept is that of the criticism of post-colonialism, where the presence of the prefix post- suggests an historical linearity and something going beyond colonialism: on the contrary, coloniality is behind the idea that this latter is still producing tangible effects, underpinned by underground and invisible procedures, in particular by way of their linguistic incorporation. For Lagomarsino, who was invited to La Criée, the Rennes art centre, this summer: “The colonial past is not a past; it’s part of our contemporary life. […] Modernity hides coloniality behind its darker side, in other words, coloniality is constitutive of modernity–there is no modernity without coloniality.”5 The work of Runo Lagomarsino–born in Argentina into an Italian family which fled fascism between the wars and then migrated to Sweden during the Argentinian dictatorship–is imbued with an autobiographical dimension which attests to his frequent to-ing and fro-ing between the two continents; the issue of migration and its variants, which he regards as one of the direct consequences of colonialism, is central to this artist’s œuvre. We all laughed at Christopher Columbus (2003) consists in the projection of the title’s words on a sheet of MDF. The sentence in question is the remake of a popular expression taken from a jazz song, whose content he appropriated (“they all laughed at Christopher Columbus when he said the world was round”): the ‘they’ became ‘we’, which prompts us to question the place of this ‘we’, but also to show how the colonial past is introduced into our vision of the world by way of the vernacular culture, preventing us from discerning its share of obscurity therein. A work also shown in Rennes once again presents the figure of the Genoese navigator: in this video (More Delicate Than the Historian’s are the Map Maker’s Colours), the artist, in cahoots with his accomplice father, gets involved in a standard hazing of the gigantic statue of Columbus, created for the Seville world fair. Using those same eggs which form the leaven of the legend of the native of Genoa to pelt the fellow, this work deals in an allusive and burlesque way with the Colombian mythology, getting those eggs to make the same voyage as the navigator’s odyssey, but in reverse, from Buenos Aires to Seville, following the route taken by his parents. The derisory nature of this ‘lite’ vandalism is a questioning of the possibility of attacking the hegemony of a seemingly unshakeable myth. The modus operandi chosen by Lagomarsino appears to signify that brutal monumentality can only be contrasted with symbolic actions, Don Quixote-like raids against the battle tanks of the official version. Another of his works takes the path of metonymy to illustrate the migrants’ drama: Sea Grammar (2015) shows an overhead view of the Strait of Gibraltar. A first hole, then another, and another, pierce the slide each time the carousel moves forward, until these perforations end up by completely blacking out the strait. Immediately conjuring up all those who have perished in the Mediterranean, Sea Grammar calls to mind the expression used by sailors when their fellow-mariners are swept away by waves: “making a hole in the sea”. This “sea grammar” is also its new litany, one that every day sees its new batch of sacrificial victims borne away by the deep, and one that has for a long time rung in the ears of amnesiac Europeans…

Runo Lagomarsino, Sea Grammar, 2015. Dia Projection loop, 80 perforated images in a slide projection carousel with timer, 1 original image. Variable projection size. Photo : Andreas Meck and Terje Östling. Courtesy Runo Lagomarsino ; Nils Staerk, Copenhagen ; Mendes Wood DM, São Paulo.

Runo Lagomarsino, More Delicate than the Historians Are the Map Maker’s Colours, 2012-2013. HD video, 6’18 min. Photo : Carla Zaccagnini. Courtesy Runo Lagomarsino ; Nils Staerk, Copenhagen ; Mendes Wood DM, São Paulo.

Take a Walk on the Wild Side

Héctor Zamora, «La réalité et autres tromperies», Frac des Pays de la Loire, 2015. Trailers and wood. Photo : Fanny Trichet

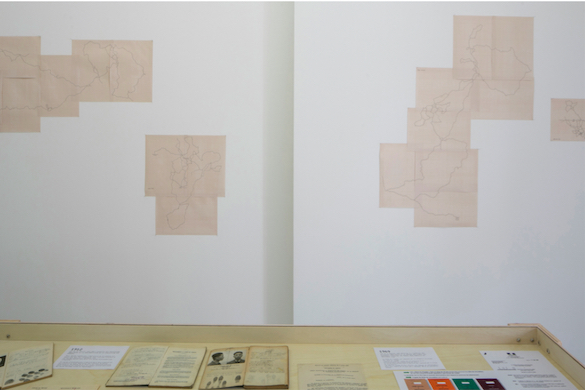

Like more shocking works, such as Vik Muniz’s paper boat, titled Lampedusa, which was on view at the Venice Biennale plying the waters of the lagoon, and Barthélémy Toguo’s piece Road to Exile (2008), Hector Zamora’s work is situated in a very head-on relation to the issue of migrants, but without going as far as the very literal illustration which Banksy produced in last summer’s parody of Disneyland, which was given a great deal of media attention, Dismaland, and Adel Adessemed’s outright macabre work, Hope (2011-2012), which uncompromisingly and straightforwardly illustrates the drama of the migrants. The installation set up at the FRAC des Pays de la Loire by the Mexican artist was somewhat radical in its overall approach: composed of seventeen secondhand caravans found in the environs, Zamora’s piece, which is egregiously simple in its arrangement, saturated the space of the FRAC’s main room, and in it traced a laborious path through the trailers. The labyrinthine dimension of the installation added to the claustrophobic feeling created by the masking of the space’s large windows, as well as the caravans’ windows, blocked out by crude bits of wood placed over them. If the caravans call to mind the gypsies, Roma and other nomads whom we are more accustomed to meeting on roads than refugees fleeing the conflicts in the Middle East, the powerful and oppressive symbolism of this piece evokes the basic obstacle to the free movement of people and the impasses in which these collateral victims of globalization find themselves bogged down in—retention areas and holding camps—preventing them from continuing their journey. Another exhibition which was held this summer at the FRAC Lorraine, “Tous les chemins mènent à Schengen” [All Roads Lead to Schengen], reverted to the issue of “travellers” and the treatment reserved for these mainly French citizens throughout the 20th century and especially during the Second World War. These travellers’ movements in the region were used as a matrix for Mathieu Pernot’s work, Le dernier voyage [The Last Journey] (2007), which produced out of them a series of spare layouts, representing a by-default history of this community which has no written documents. What is more, the archival work bringing together a large number of documents and the famous anthropometric logbooks, which these French citizens had to present to the authorities, manages to shed light on the arbitrary nature of the ‘special’ treatment meted out to these people throughout the century. The choice of the exhibition is to place the phenomena associated with migration (in the broad sense) in the rather unexpected light of the walk which, on reflection, turns out to be quite relevant: what in fact is the common denominator of all these candidates for exile, those migrating for economic reasons, and those fleeing the world’s troubled regions, if not the need, at a given moment, to cover long distances on foot, using mountain paths, crossing stony deserts and taking every manner of byway? The show alternates sequences bordering on the absurd, like Bouchra Khalili’s now classic Mapping Journey Project (2008-2011), where we witness the stoic comments of the migrants before setting out to cover thousands of additional miles on top of the ‘normal’ itinerary, with the documentary films of Ursula Niemann, which consist in an in-depth investigation of the huge trading system represented by migration, its economy, its smugglers, and the various hubs and other contact areas which create a structure from one end of the immense Sahara to the other (Sahara Chronicles, 2006-09). But the exhibition also allows itself to move away from the dramatic tone with a little video gem showing the small town of Schengen with all the neat and tidy array of a pleasant, carefree place in Luxembourg, visited by lots of tourists since the Agreement was signed in 1985, seemingly totally indifferent to the tragedy being played out under its auspices (Justine Blau, Schengenland, 2011). Last of all, taking the expression literally, a series of walks (Take a Walk on the Wild Side) between Metz and Schengen was organized throughout the exhibition, some using the route taken by asylum-seekers from prefectures to accommodation centres, others in the much more playful and anything but dramatic vein of the simple pleasure of walking.

Runo Lagomarsino, We All Laughed at Christopher Columbus, 2003.

Single slide projection on MDF, 45,5 × 25,5 × 42,5 cm. Photo : Ken Adlard. Courtesy Runo Lagomarsino ; Nils Staerk, Copenhagen ; Mendes Wood DM, São Paulo.

The issue of migrants, or rather migration—because talking about migrants rather than refugees already offers a clue about the fact of knowing where one is speaking from—brings the ‘controversy’ about art and politics centre stage, once more. It would nevertheless seem that this pair—even if it is no longer based on an exploitation of the former at the service of the latter, and even if it is broadly free of any kind of teleological dimension—is still stimulating artistic production in our day and age and that this art, rooted in the world’s realities, is still producing ‘valid’ forms, well removed from any formalism, but without wanting to turn its back on the seductions of new forms of matter and new technologies (including information). All of which shows quite simply that it is absurd to try and separate the two, at the risk of accentuating varieties of formal extremism and a nostalgia for a mythical revolutionary golden age… The fact that this art is often directly related to language and words, which it presents by borrowing types of vernacular appearance, is no longer surprising, either, given the fact that words are the principal vehicles of cultural representations and their forms of imagination, which, in a painless way, spread through the social corpus. The migratory issue is merely prolonging other fractures, be they colonial, racial, north/south, to do with gender, and so on, which are being explored by the notion of coloniality. The ‘natural’ obstacles which have to be overcome by candidates for exile in the western land of milk and honey are perhaps not the most insurmountable, compared with the cultural borders which await them… This, in particular, is the turf of the special game being played by an art which is still concerned with things human.

Mathieu Pernot, Le dernier voyage (détail), 2007. Exhibition view: Tous les chemins mènent

à Schengen, 49 Nord 6 Est- Frac Lorraine, Metz, 2015. Photo : E. Chenal © Mathieu Pernot

1-“It is not a matter of putting poetry at the service of the revolution but rather of putting the revolution at the service of poetry. It is only in this way that the revolution does not betray its project. We will not repeat the mistake of the Surrealists putting themselves at its service when, precisely, there was no longer any revolution”. “All the King’s Men”, Internationale Situationiste, n°8, January 1963, p. 31, quoted by Anne Trespeuch-Berthelot in L’internationale Situationiste. De l’Histoire au Mythe, p. 78 et sq.

2-“And once there are greater imbalances of interests and dissension cannot be solved in a unitary measure, the freedom experienced in the lack of measure lies at the very root of politics and art. Art and politics meet each other here, if we understand that politics is not measured solely by its argumentative capacity to reveal social relations with a view to a revolutionary strategy. Being political is first of all not to recognize oneself in the world as it is, and to recognize that one is in a situation where it is possible to shift lines, bodies, deeds and words, spaces and times, etc.; it is situating oneself in the capillarity of the perceptible, down to the smallest things.” Claude Amey, Art / Politique, Les éditions de la maison chauffante, 2010, p. 61.

3 Barry Malone, “Why Al Jazeera will not say Mediterranean ‘migrant’. The word migrant has become a largely inaccurate umbrella term for this complex story.” http://www.aljazeera.com/blogs/editors-blog/2015/08/al-jazeera-mediterranean-migrants-150820082226309.html

4 Le Monde des livres dated 6 November 2015, a dossier on power, special forum philo.

5 Walter Mignolo quoted by Lagomarsino in “Question & Answer with Runo Lagomarsino”, in kunstforum.as, 7 April 2014.

- From the issue: 76

- Share: ,

- By the same author: Curator’s marathon : Frac Sud, Mucem, Mac Marseille, Where have all those reviews gone?,

Related articles

Paris noir

by Salomé Schlappi

Some white on the map

by Guillaume Gesvret

Toucher l’insensé

by Juliette Belleret