Jason Loebs, Pamela Rosenkranz, Cheyney Thompson

Des peintures et des hommes

Il est une question qui préoccupe l’homme depuis au moins quelque cent vingt mille ans [1] et parcourt ainsi l’histoire de la pensée : celle de la médiation de l’immatériel par le matériel. L’objet physique semble avoir toujours été considéré comme un adjuvant nécessaire à la réflexion métaphysique populaire [2] (en effet, l’aniconisme voire l’iconoclasme prônés par certaines doctrines n’excluaient pas, par exemple, l’édification de tombeaux) et, des alignements et autres agencements mégalithiques au veau d’or mythologique, en passant par les nécropoles antiques et les cathédrales gothiques, la manifestation de l’abstrait tient une place prépondérante dans l’ensemble des productions humaines.

Un saut dans le temps nous apprendra que les choses n’ont pas sensiblement changé, l’art n’a de cesse de s’emparer de ces questions tout autant que de celles traditionnellement dévolues à la physique et aux mathématiques comme l’entropie, la perception… Et les grands dualismes supposément irrésolubles corps / esprit, nature / culture, etc. — d’ailleurs contestés par les récentes expositions « Descartes’Daughter » [3] et « Nature After Nature » [4] (le statement de Susanne Pfeffer pour cette dernière présentant une nouvelle acception du terme « nature », une nature intégrant l’homme et son environnement dans sa totalité, rejetant les différenciations entre synthétique et organique, artificiel et naturel) — continuent d’infuser le travail de nombre d’artistes. À ces interrogations éternelles se mêlent celles, plus récentes, afférentes à l’abstraction grandissante de notre environnement (du capital, du travail, des réseaux sociaux, des images, de la musique… Bref, de la totalité des chaînes de création de valeur). Aussi, depuis que le capitalisme a délaissé les principes fordistes d’organisation hiérarchique du travail pour en développer une organisation en réseau (l’évolution sémantique du terme est d’ailleurs tout à fait passionnante : du « filet destiné à capturer certains animaux » à « l’ensemble de tout ce qui peut emprisonner l’homme, entraver sa liberté, menacer sa personnalité » en passant évidemment par « l’entrecroisement des voies de passage » et « l’ensemble de voies de communication » [5] ) basée sur des investissements essentiellement immatériels (temps, capital financier et capital humain), c’est dans « le tissu sans couture du réseau » [6], par essence perméable, que circulent désormais les flux.

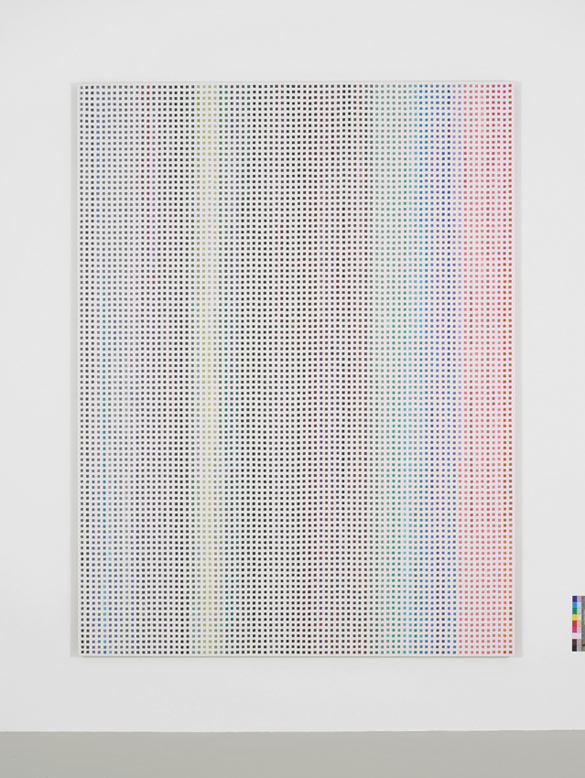

Ces flux, naturels ou artificiels, physiques ou théoriques, semblent ramener celui qui les pense à la fixité d’un point, à la passivité d’un être contingent. Tandis que notre existence n’influe absolument pas sur certains de ces flux, nous nous plaisons à penser que nous pouvons encore en maîtriser certains autres. Les flux de capitaux sont de ceux-là. Emplissant les toiles apprêtées des Stochastic Process Paintings de Cheyney Thompson, de petits carrés d’un centimètre carré scandent la surface blanche d’une présence obsessive. Suite presque logique des Chromachromes (2009) et des Chronochromes (2009-2011) [7] pour lesquels le peintre utilisait déjà le système colorimétrique d’Albert Munsell (répartition des couleurs par teinte, valeur et saturation) afin de déterminer des paires de couleurs complémentaires, cette nouvelle série intègre un degré supplémentaire d’aléatoire dans ce choix : Thompson a en effet intégré un algorithme qui relève du calcul des probabilités à l’espace tridimentionnel de Munsell. En se développant au cœur de ce volume de couleurs, la courbe pointe différentes teintes, valeurs et saturations que l’artiste traduit ensuite en nuances physiques minutieusement appliquées à la main. L’algorithme, qui porte le joli nom de « la marche de l’ivrogne » [8] et dont l’usage traditionnel, appliqué au domaine financier, est de prédire des cotes, apparaît ici comme une illustration de lui-même, privé qu’il est dans ce cadre de son efficience réelle quant aux flux abstraits des marchés financiers. L’impression de regarder une trame numérique sur laquelle on aurait zoomé n’est pas si éloignée non plus du motif des Chroma- et Chronochromes qui reprenait l’image d’un morceau de toile agrandie et répétée pour s’étendre sur toute la surface des tableaux. Cependant, il ne s’agit plus d’une autoréflexivité aussi littérale, les Stochastic Process Paintings cessent de redoubler leur propre matérialité et l’on pourrait même dire en un sens qu’elles la dépassent en refusant, par leur facture relativement neutre — ni parfaitement nette et artificielle comme une peinture au scotch ou une impression sur toile, ni franchement déliée et encore moins spontanée — le plaisir visuel que pouvait apporter l’aspect plus organique des Chroma- et Chronochromes. La qualité de cette répétitivité n’est pas sans rappeler celle mise en œuvre par Olivier Mosset dans ses cercles ou par Niele Toroni dans ses Empreintes de pinceau — ici aussi les « intervalles sont réguliers » — cependant la délégation décisionnelle du choix des couleurs à une instance extérieure ainsi que la vertigineuse inclusion sur le mode du possible de l’ensemble des couleurs de l’atlas de Munsell [9] placent ces peintures à la jonction d’un monde mathématique « où les corps comme leurs mouvements sont descriptibles indépendamment de leurs qualités sensibles — saveur, odeur, chaleur, etc. » [10] et d’un monde dont la physicalité trahit l’humanité [11], où elles peuvent persister à poser cette question de l’écart qui règne entre la fiction produite par un système et son incarnation dans la réalité. [12]

Cheyney Thompson, Stochastic Process Painting2, 2014 Huile sur toile / Oil on canvas, 207 x 156 cm. Courtesy Campoli Presti, London / Paris.

De prime abord, c’est un aspect tellurique comme contraint, bridé, qui frappe à la vue des peintures de Jason Loebs. Une impression de densité qui provoque une envie tactile. Et c’est presque logique : ces « peintures » sont réalisées avec de la graisse thermique à base de graphite appliquée sur toile enduite. Sachant que cette graisse est un conducteur thermique utilisé dans l’électronique et l’informatique notamment pour transférer l’excès de chaleur émis par un composant vers un dissipateur, elle capte la chaleur des corps qui l’entourent, qu’ils soient humains ou non. La thermodynamique (branche de la physique qui étudie les échanges entre les diverses formes d’énergie et traite des états et des propriétés de la matière) infuse l’ensemble du travail de Loebs et lui permet de poser la question du rapport entre l’entropie et la production d’images. Par cette série de tableaux, il inscrit délibérément cette interrogation dans le cadre de l’histoire de la peinture, évoquant le fait que jusqu’au xxe siècle, les peintres étaient très au fait des techniques, au sens matériel du terme, puis qu’avec l’apparition des peintures synthétiques, c’est tout un pan de ce savoir qui a été délaissé. Comme un clin d’œil au Carré noir sur fond blanc (1915) de Malevitch à la lisséité monochromatique désormais zébrée de craquelures, peut-être réalisé sans conscience ou volonté de durabilité — mais, après tout, la stabilité n’est-elle pas l’antonyme de la révolution ? — les « graisse sur toile » de Jason Loebs sont pensées pour ne jamais sécher et, ainsi, mettre en avant l’échange continuel de l’œuvre avec l’atmosphère. S’il s’agit d’un côté, selon lui, de « réintroduire la dimension minérale dans la peinture » en écho à cette connaissance classique des pigments minéraux évoquée plus haut, il s’agit surtout de pointer, comme dans tout son œuvre d’ailleurs, que l’histoire du développement technique et technologique sans précédent que nous connaissons depuis le xixe siècle se base sur une exploitation des ressources naturelles au service de la production de valeur et d’instruments de contrôle de l’homme. La « domestication de l’entropie » [13] a en effet enclenché la révolution industrielle mais certaines théories récentes développées notamment par un astrophysicien français donnent les lois de la thermodynamique comme plus fondamentales encore et, surtout, applicables à l’analyse de l’évolution des sociétés humaines. [14]

L’intérêt de Loebs pour la chaleur qu’il définit comme « un gradient entre un corps et un autre », comme « la mesure de ce qui est en soi immesurable » et non comme une « forme objective » [15]révèle que l’énergie est un flux dont la conception est elle-même aussi fluctuante.

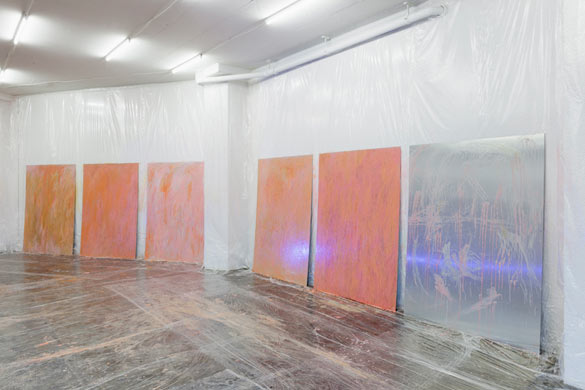

Pamela Rosenkranz, vue de l’exposition / Installation view « My sexuality », 2014 Karma International. Courtesy Karma International & Pamela Rosenkranz. Photo : Gunnar Meier.

Des préoccupations assez proches ont été exposées par le philosophe Reza Negarestani dans les textes qu’il a écrits pour les catalogues de Pamela Rosenkranz [16] situant le travail de cette dernière dans les espaces réinterprétés par la science moderne qui, auparavant, pouvaient être consiédérés commes les bastions du penseur et du créateur (pensée, intuition, imagination…), l’amenant à repenser l’œuvre d’art comme déjà en germe dans l’univers [17]. Depuis 2005, l’œuvre de la Suissesse interroge en effet la « solidarité anthropocosmique » [18], c’est-à-dire la nécessité du lien entre l’homme et l’univers, avec un fort penchant nihiliste. C’est aussi par là la question du « soi » et, plus généralement, le mind-body problem qui affleure dans des pièces comme The Most Important Body of Water is Yours (2001) soulignant que notre corps étant composé de 50% d’eau (et notre cerveau d’environ 70%), ce nous que nous appelons « je » appartiendrait tout autant à l’univers qu’à nous… Sa dernière exposition personnelle en date [19] l’évoquait à nouveau avec une littéralité troublante : murs et sol de la galerie Karma International avaient été recouverts d’un film plastique transparent et, au cœur de l’espace ainsi protégé, provoquant la désagréable sensation d’un environnement aussi peu sympathique qu’une barquette de viande sous vide, se dressaient des panneaux d’aluminium aux dimensions sensiblement humaines, couverts de traces de peinture couleur chair. Non sans évoquer la série As One (2010), des panneaux de verre acrylique moulé se tenant debout, similairement barbouillés, les Sexual Power (Viagra Paintings 1-11)(2014) surjouaient la physicalité dans une impression générale de violence contenue. La rigidité des panneaux d’aluminium qui semblait tenter d’assagir les traces de ce qui s’était passé à leur surface — contrastant avec la relative douceur des lignes habituellement présentes dans le travail de l’artiste : souplesse du spandex d’Avoid Contact (2011), formes curvilignes des bouteilles de PET de Firm Being… — et leur format rappelant ceux de grandes toiles ne pouvaient nous empêcher de penser que Rosenkranz se plaisait ici à singer les ténors de l’expressionnisme abstrait. Pour mieux se jouer de cette peinture gestuelle essentiellement masculine, elle avait ingéré du Viagra avant de peindre, directement à la main. L’in situ de la séance était signalé par les dégoulinures d’acrylique sur le film plastique quant au rendu pictural, il tendait vers le résultat d’un combat de l’artiste avec elle-même ; avec ou contre ce « soi » ?

À l’échelle de l’histoire du cosmos, celle de la présence humaine en son sein est, on le sait bien, singulièrement brève. Que le mouvement de l’énergie excédentaire donne lieu dans son histoire à de pures pertes comme à de grandes avancées, la canalisation des flux dans des formats restreints est une ambition humaine immémoriale et une tentative artistique parfaitement contemporaine.

- ↑ Quelque cent vingt mille ans c’est, à ce jour, la datation approximative de la plus ancienne sépulture connue, située en actuel Israël.

- ↑ Entendons par là la réflexion de tout un chacun concernant les questions fondamentales telles que l’existence de l’âme et son immortalité, Dieu, la finitude de l’homme, etc. que l’on distingue ici de celle menée par les philosophes.

- ↑ « Descartes’Daughter », Swiss Institute, New York, du 20 septembre au 3 novembre 2013, avec Malin Arnell, Miriam Cahn, John Chamberlain, Hanne Darboven, Melanie Gilligan, Rochelle Goldberg, Nicolàs Guagnini / Jeff Preiss, Rachel Harrison, Lucas Knipscher, Jason Loebs, Ulrike Müller, Pamela Rosenkranz, Karin Schneider, Sergei Tcherepnin, Charline von Heyl, commissariat : Piper Marshall. S’appuyant sur l’anecdote de la fabrication par le philosophe d’une poupée à l’effigie de sa fille décédée pour pallier son chagrin, l’exposition se donnait comme une réponse aux catégorisations de l’œuvre d’art soit comme expression physique soit comme expression psychique et un écho aux récents développements philosophiques du rapport entre matière et essentialisme.

- ↑ « Nature After Nature », Fridericianum Kassel, du 11 mai au 27 juillet 2014, avec Olga Balema, Juliette Bonneviot, Björn Braun, Nina Canell, Alice Channer, Ajay Kurian, Sam Lewitt, Jason Loebs, Marlie Mul, Magali Reus, Nora Schultz, Susanne M. Winterling, commissariat : Susanne Pfeffer.

- ↑ Extraits des définitions du terme « réseau » données par le centre national de ressources textuelles et lexicales.

- ↑ Luc Boltanski et Eve Chiapello, Le nouvel esprit du capitalisme, Paris, Gallimard, 1999, p. 157.

- ↑ Pour plus de détails à ce sujet, cf. Aude Launay, « Cheyney Thompson, Un système contre le système », 02 n°56, hiver 2010, p. 19-22.

- ↑ La marche aléatoire est « un modèle mathématique d’un système possédant une dynamique discrète composée d’une succession de pas aléatoires […] à chaque instant, le futur du système dépend de son état présent, mais pas de son passé, même le plus proche. Autrement dit, le système “perd la mémoire” à mesure qu’il évolue dans le temps. Pour cette raison, une marche aléatoire est parfois aussi appelée “marche de l’ivrogne”. […] C’est par exemple la méthode utilisée par le moteur de recherche Google pour parcourir, identifier et classer les pages du réseau internet. (wikipédia)

- ↑ Cf. Simon Baier, « Dead Time Painting », in Cheyney Thompson, metric pedestal cabengo landlord récit, MIT List Visual Center, Cambridge et Koenig Books, Londres, p. 179.

- ↑ Quentin Meillassoux, Après la finitude, Paris, Seuil, 2012, p. 171.

- ↑ Cette physicalité s’exprime tant dans la multitude de couleurs et l’expérience « optique » qui en résulte que dans, par exemple, les récentes sculptures de l’artiste (série des Broken Volume, 2013), transcription en béton du chemin d’un petit cube tracé par le même algorithme. Bien évidemment, sans structure interne, elles ploient sous leur propre poids allant parfois jusqu’à la cassure exemplifiant ainsi l’irréductibilité du fossé entre l’espace mathématique dans lequel il n’y a ni gravité, ni friction et l’espace physique que ces phénomènes contribuent à constituer.

- ↑ Ann Lauterbach, dans le texte qu’elle a produit pour la monographie de l’artiste exprime brillamment ce rapport à l’entre-deux : « We begin to think that meaning can only arise as a condition of prepositional relation : between, among, with, of, in. » in Cheyney Thompson, metric pedestal cabengo landlord récit, op. cit., p. 175.

- ↑ « […] indeed, techne is a sort of domesticated entropy », Matteo Pasquinelli, « Four Regimes of Entropy », in Jason Loebs : Title Stack Sink Release, Fri Art, Fribourg, 2014.

- ↑ Voir à ce sujet : François Roddier, Thermodynamique de l’évolution, Un essai de thermo-bio-sociologie, Parole éditions, 2012, et « La thermodynamique des sociétés humaines », 2014.

- ↑ Jason Loebs, « Rubbing the wrong way back », in Jason Loebs : Title Stack Sink Release, op. cit.

- ↑ Reza Negarestani, « Solar Inferno and the Earthbound Abyss », in Pamela Rosenkranz, Our Sun, Instituto Svizzero di Roma, Mousse Publishing Milano, 2010 et « Darwining the Blue » in Pamela Rosenkranz, No Core, JRP Ringier, 2012.

- ↑ Reza Negarestani, in Pamela Rosenkranz, No Core, op. cit., p. 129.

- ↑ Gilbert Hottois, « Technoscience et principe de raison », Studia Leibnitiana, Leibniz : le meilleur des mondes, actes d’une table-ronde organisée par le CNRS et la Gottfried-Wilhelm-Leibniz-Gesellschaft en 1990, Steiner, 1992, p. 44.

- ↑ Pamela Rosenkranz, « My Sexuality », Karma International, Zurich, du 14 juin au 26 juillet 2014.

Of Paint and Men

Jason Loebs, Pamela Rosenkranz, Cheyney Thompson

There is a question that has been exercising people for at least 120,000 years [1], and thus runs through the history of thought: the conveyance of the immaterial by the material. The physical object seems to have always been regarded as a necessary auxiliary to popular metaphysical reflection [2] (in fact the aniconism not to say iconoclasm advocated by certain doctrines did not, for example, bar the building of tombs) and, from megalithic alignments and similar arrangements to the mythological golden calf, by way of antique necropolises and Gothic cathedrals, the manifestation of the abstract has a predominant place in the overall set of human productions.

A leap in time will tell us that things have not changed that much, art is forever appropriating these issues just as much as those traditionally assigned to physics and mathematics, such as entropy, and perception… And the great and supposedly unsolvable dualisms, body/mind, nature/culture, and so on—incidentally disputed by the recent exhibitions Descartes’ Daughter [3] and Nature After Nature [4] (with Susanne Pfeffer’s statement for the latter introducing a new accepted sense of the term “nature”, a nature encompassing man and his environment in its entirety, thus rejecting differentiations between synthetic and organic, artificial and natural)—are still informing the work of many artists. Mingling with these eternal questions are more recent ones to do with the growing abstraction of our environment (capital, labour, social networks, images, music… in a word, all the value-creating processes). So since capitalism abandoned the Fordist principles governing the hierarchical organization of labour, and developed a networked organization (the semantic evolution of the term ‘network’ is, incidentally, extremely interesting: from the “net designed to catch certain animals” to “anything that can imprison man, obstruct his freedom, threaten his personality” by way, obviously enough, of the “intersection of thoroughfares” and “every manner of communication channel”) [5], it is within the “seamless fabric of the network”, [6] which is essentially permeable, that flows now circulate.

These flows, be they natural or artificial, physical or theoretical, seem to take anyone thinking about them to the fixedness of a point, to the passiveness of a contingent being. While, for some of these flows, our existence has absolutely no effect on theirs, for others, we like to think that we can still control them. Capital flows are among the latter. Filling the primed canvases of Cheyney Thompson’s Stochastic Process Paintings, small squares measuring a square centimetre punctuate the white surface with an obsessive presence. As an almost logical sequence to the Chromachromes (2009) and the Chronochromes (2009-2011) [7] for which the painter was already using the Munsell colour system (distribution of colours by hue, value and chroma (saturation)) in order to determine pairs of complementary colours, this new series incorporates an additional degree of randomness in this choice: Thompson has actually integrated an algorithm that stems from the calculation of probabilities in Munsell’s three-dimensional space. By developing at the core of this volume of colours, the curve pinpoints different hues, values and saturations which the artist then interprets in physical nuances painstakingly applied by hand. The algorithm, which is cutely named “the drunken walk” [8] and whose traditional use, applied to finance, is to predict rates, here appears like an illustration of itself, deprived as it is, in this context, of its real effectiveness with regard to the abstract flows of financial markets. The impression of looking at a digital grid that has been zoomed in on is not that far removed, either, from the motif of Chroma- and Chronochromes which borrowed the image of a piece of canvas, enlarged and repeated, until it covered the entire surface of the pictures. But what is involved is no longer such a literal self-reflexiveness; the Stochastic Process Paintings stop duplicating their own material nature and we might even say, in a way, that they go beyond it by refusing, through their relatively neutral style—neither perfectly distinct and artificial like a painting using adhesive tape or a print on canvas, nor altogether spontaneous—the visual pleasure that could be ushered in by the more organic aspect of the Chroma- and Chronochromes.

Jason Loebs. Untitled, 2014. Graisse thermique sur toile / thermal grease on canvas, 157.48 x 111.76 x 5.08 cm, (droite/right, detail). Courtesy Jason Loebs ; Essex Street, New York.

The quality of this repetitivity calls to mind that applied by Olivier Mosset in his circles, and by Niele Toroni in his Empreintes de pinceau — here, too, the “intervals are regular” —, but the delegation of decisions to do with the choice of colours to an outside agency, as well as the dizzy-making inclusion, in the mode of the possible, of all the colours in the Munsell atlas [9] place these paintings at the junction of a mathematical world “where bodies and their movements can be described independently of their perceptible qualities—taste, smell, warmth, etc. [10]” and a world whose physicality betrays its humanity, [11] where they can go on raising this issue of the gap that reigns between the fiction produced by a system and its incarnation in reality. [12]

At first glance, there is a telluric aspect, as if restricted and bridled, which strikes you when you look at Jason Loebs’s paintings. An impression of density which gives rise to a tactile desire. And this is almost logical: these “paintings” are made with graphite-based thermal grease applied to primed canvas. Knowing that this grease is a heat conductor used in electronics and computer technology in particular to transfer the excess of heat emitted by a component towards a dissipator, it captures the heat of the bodies surrounding it, be they human or other. Thermodynamics (that branch of physics which examines the exchanges between the various forms of energy and deals with the states and properties of matter) imbues the whole of Loebs’s work and enables him to raise the issue of the relation between entropy and image production. Through this series of pictures, he deliberately includes this question within the framework of the history of painting, evoking the fact that up until the 20th century, painters were very well informed about techniques, in the material sense of the term, and then that with the appearance of synthetic paints, a whole swathe of that knowledge was left behind. Like a wink at Malevich’s Black Square (1915), at the monochromatic smoothness now fissured with cracks, perhaps made unwittingly or without any desire for permanence—but, after all, is stability not the antonym of revolution?—Jason Loebs’s “grease on canvas” works are devised to never dry and, in this way, to emphasize the ongoing exchange between work and atmosphere.

On the one hand, according to him, it is a question of “reintroducing the mineral dimension into painting”, echoing that classical knowledge about mineral pigments mentioned above, and it is a question above all of pinpointing, as in all his work, incidentally, the fact that the history of the unprecedented technical and technological development that we have known since the 19th century is based on an exploitation of natural resources at the service of a production of value and instruments designed to control human beings. The “domestication of entropy” [13] did in fact trigger the industrial revolution but certain recent theories developed in particular by a French astrophysicist see the laws of thermodynamics as even more fundamental and, above all, applicable to the analysis of the evolution of human societies [14]. Loebs’s interest in heat, which he defines as a “gradient between one body and another”, as “the measurement of that which is immeasurable in itself” and not as an “objective form” [15], reveals that energy is a flow whose conception is itself fluctuating, too.

Quite similar preoccupations have been set forth by the philosopher Reza Negarestani in the texts he has written for Pamela Rosenkranz’s catalogues [16], situating this latter’s work in spaces re-interpreted by modern science which, previously, might be regarded as the bastions of the thinker and the creator (thought, intuition, imagination…), leading him to re-think the work of art as already embryonic in the world [17]. Since 2005, the Swiss artist’s work has in fact been questioning “anthropocosmic solidarity” [18], meaning the need for the link between man and the universe, with a marked nihilist bent. This is also where the issue of the “self” and, more generally, the mind-body problem, comes to the fore in pieces like The Most Important Body of Water is Yours (2001), emphasizing that because our body is made of 50% water (and our brain of about 70%), what we call “the self” belongs just as much to the universe as to ourselves… Her latest solo show to date [19] referred to this once again with a disturbing literalness: walls and floor of the Karma International gallery had been covered with a see-through plastic film and, at the heart of the thus protected area, creating the unpleasant sensation of an environment as nasty as a vacuum-packed container of meat, there rose up aluminium panels with markedly human dimensions, covered with traces of flesh-coloured paint. Calling to mind the series As One (2010), moulded acrylic glass panels standing upright, similarly smeared, the Sexual Power (Viagra Paintings 1-11) (2014) overplayed the physical aspect in a general impression of contained violence. The rigidity of the aluminium panels, which seemed to be trying to allay the traces of what had come to pass on their surface—contrasting with the relative softness of the lines usually present in the artist’s work: suppleness of the spandex in Avoid Contact (2011), curved forms of PET bottles in Firm Being… — and their format calling to mind those of large canvases could not stop us thinking that Rosenkranz was taking pleasure here in aping the big names of abstract expressionism. The better to play with this essentially masculine gestural painting, she had swallowed some Viagra before painting, directly by hand. The in-situ nature of the session was indicated by the streaks of acrylic on the plastic film; as far as the pictorial rendering was concerned, this tended towards the outcome of a combat between the artist and herself; with or against this “self”?

On the scale of the history of the cosmos, the history of human presence within it is, as we well know, particularly short. Because the movement of surplus energy gives rise, in the human history, to pure losses as well as great advances, the channelling of flows in restricted formats is an age-old human ambition and a thoroughly contemporary artistic —and particularly pictorial— attempt.

- ↑ 120,000 years, give or take, is, as of this writing, the approximate dating of the oldest known burial place, located in present-day Israel.

- ↑ What we mean by this is the reflection by anyone and everyone about fundamental issues such as the existence of the soul and its immortality, God, the finiteness of man, etc., which is distinct, here, from the reflection undertaken by philosophers.

- ↑ “Descartes’ Daughter”, Swiss Institute, New York, from 20 September to 3 November 2013, with Malin Arnell, Miriam Cahn, John Chamberlain, Hanne Darboven, Melanie Gilligan, Rochelle Goldberg, Nicolàs Guagnini / Jeff Preiss, Rachel Harrison, Lucas Knipscher, Jason Loebs, Ulrike Müller, Pamela Rosenkranz, Karin Schneider, Sergei Tcherepnin, and Charline von Heyl, curated by : Piper Marshall. Based on the anecdote of the philosopher making a doll just like his deceased daughter to relieve his grief, the exhibition came across as a response to the pigeonholing of the work of art either as a physical expression or as a psychic expression, echoing recent philosophical developments of the relation between matter and essentialism.

- ↑ “Nature After Nature”, Fridericianum Kassel, from11 May to 27 July 2014, with Olga Balema, Juliette Bonneviot, Björn Braun, Nina Canell, Alice Channer, Ajay Kurian, Sam Lewitt, Jason Loebs, Marlie Mul, Magali Reus, Nora Schultz, and Susanne M. Winterling, curated by: Susanne Pfeffer.

- ↑ Extracts of definitions of the term “network” provided by the Centre national de ressources textuelles et lexicales.

- ↑ Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello, Le nouvel esprit du capitalisme, Paris, Gallimard, 1999, p. 157.

- ↑ For further details on this, cf. Aude Launay, “Cheyney Thompson, A system against the system”, 02 n°56, winter 2010, p. 19-22.

- ↑ The random walk is “a mathematical formalization of a path that consists of a succession of random steps. For example, the path traced by a molecule as it travels in a liquid or a gas, the search path of a foraging animal, the price of a fluctuating stock and the financial status of a gambler can all be modeled as random walks, although they may not be truly random in reality”. Otherwise put, the system “loses its memory” as it evolves in time. This is why a random walk is sometimes also called a “drunken walk”. (wikipedia)

- ↑ Cf. Simon Baier, “Dead Time Painting”, in Cheyney Thompson, metric pedestal cabengo landlord récit, MIT List Visual Center, Cambridge and Koenig Books, London, p. 179.

- ↑ Quentin Meillassoux, After Finitude: An Essay On The Necessity Of Contingency, trans. Ray Brassier, London, Continuum, 2008.

- ↑ This physicality is expressed both in the host of different colours and the “optical” experience that results therefrom and, for example, in the arrtist’s recent sculptures (the Broken Volume series, 2013), a transcription in concrete of the route of a small cube traced by the same algorithm. Needless to say, without any inner structure, they all bend beneath their own weight, at times even breaking, thus exemplifying the irreducibility of the gap between the mathematical space in which there is neither gravity nor friction, and the physical space which these phenomena help to form.

- ↑ Ann Lauterbach, in the text that she has written for the artist’s monograph, brilliantly expresses this relation to the in-between: “We begin to think that meaning can only arise as a condition of prepositional relation : between, among, with, of, in” in Cheyney Thompson, metric pedestal cabengo landlord récit, op. cit., p. 175.

- ↑ “[…] indeed, techne is a sort of domesticated entropy”, Matteo Pasquinelli, “Four Regimes of Entropy”, in Jason Loebs : Title Stack Sink Release, Fri Art, Fribourg, 2014.

- ↑ See on this subject: François Roddier, Thermodynamique de l’évolution, Un essai de thermo-bio-sociologie, Parole éditions, 2012, and « La thermodynamique des sociétés humaines », 2014.

- ↑ Jason Loebs, “Rubbing the wrong way back”, in Jason Loebs : Title Stack Sink Release, op. cit.

- ↑ Reza Negarestani, “Solar Inferno and the Earthbound Abyss”, in Pamela Rosenkranz, Our Sun, Instituto Svizzero di Roma, Mousse Publishing Milan, 2010, and “Darwining the Blue” in Pamela Rosenkranz, No Core, JRP Ringier, 2012.

- ↑ Reza Negarestani, in Pamela Rosenkranz, No Core, op. cit., p. 129.

- ↑ Gilbert Hottois, “Technoscience et principe de raison”, Studia Leibnitiana, Leibniz : le meilleur des mondes, proceedings of a round table organized by the CNRS and the Gottfried-Wilhelm-Leibniz-Gesellschaft in 1990, Steiner, 1992, p. 44.

- ↑ Pamela Rosenkranz, “My Sexuality”, Karma International, Zurich, from 14 June to 26 July 2014.

- Partage : ,

- Du même auteur : L’histoire polyphonique du Net Art, un Eternal Network?, Le curating algorithmique, De décennies en millénaires, Smells Like Ten Spirit, Pre ➔ Post-Internet, L’objet, la chose et le n’importe quoi dans la sculpture de R.Harrison,

articles liés

Pratiquer l’exposition (un essai scénographié)

par Agnès Violeau

La vague techno-vernaculaire (pt.2)

par Félicien Grand d'Esnon et Alexis Loisel Montambaux

La vague techno-vernaculaire (pt.1)

par Félicien Grand d'Esnon et Alexis Loisel Montambaux